Suddenly, there is a lot of talk that the 10-year bond yield will return to 5%, which is ridiculous after only a few months of interest rate-cutting mania.

Written by Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

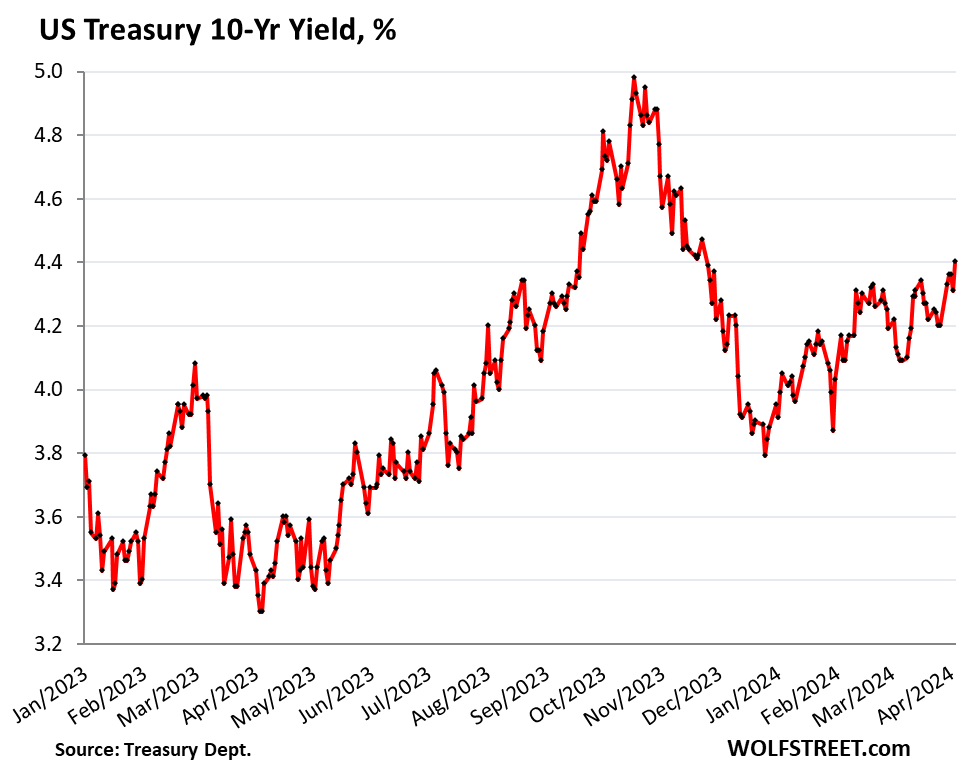

The yield on the 10-year Treasury note rose to 4.40% on Friday, the highest level since November 27. During the rate-cutting mania in December, the yield fell below 3.80%.

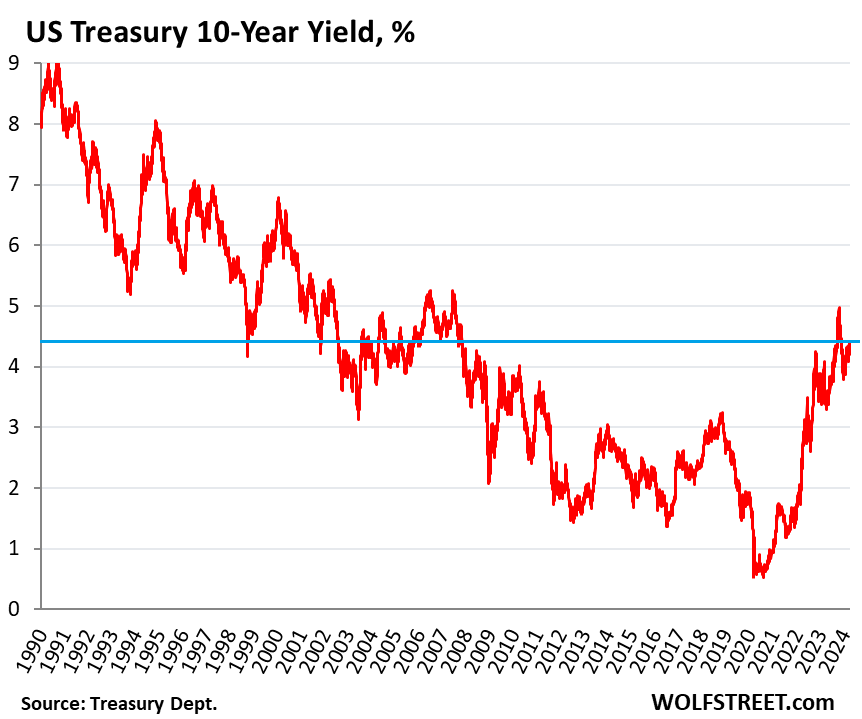

Combined in recent days and weeks, these moves signal a gradual recognition in the bond market that inflation rates will be higher than they were before the pandemic, that 2% inflation is not going to happen, and that the ultra-low interest rate environment of the past 15 years is over – Which peaked in August 2020 when the yield on ten-year bonds fell to 0.5%.

What comes next is unknown, but it will likely involve higher inflation of the kind seen in the 1990s and earlier because the Fed is not willing to crash the economy and labor market just to reach a 2% inflation rate.

This means that the Fed will keep interest rates fairly high – high enough to not let inflation get out of control, but not so high that it collapses the economy and brings inflation down to 2% – and yields will also be higher to compensate for inflation. As inflation rises, everything will be higher, as it was before, and the bond market adapts to this scenario.

Now there's suddenly a lot of talk that the 10-year yield is going to go back to 5%, where it was briefly in October, because inflation is going to be higher for longer, or forever, which is funny after the mania of cutting interest rates, and the yield was going to go up. To compensate for inflation over a 10-year period, plus some.

It is clear that the word “forever” here does not mean forever in the cosmic sense, but in the sense of a bond, that is, after the maturity date of the bond.

It's interesting how the narrative in the market has changed so quickly. From November to mid-January, there was a rate-cut mania, with the federal funds futures market seeing very high odds of five, six and even seven rate cuts in 2024, spread out over the Fed's eight meetings.

And then the Fed started to pull back. He came out with a retracting statement from the FOMC after the January meeting, and repeated it at the March meeting. We got two terrible inflation readings in January and February, in addition to the upward trend in fundamental measures that began last fall.

The “dot plot” from the March FOMC meeting showed that the 19 participants were almost evenly split, with 9 seeing two rate cuts in 2024, 9 seeing three rate cuts, and 1 seeing four cuts, leaving the average At three discounts. But if only one of the three pieces becomes a double breaker by the June dot chart, the double breaker scenario will emerge from this meeting. The “dot plot” in March was a warning sign that these three rate cuts might be going away.

Since then, several Fed officials have given speeches, expressed concern about the path of inflation, and backed away from their own expectations for rate cuts.

Yesterday, Minneapolis Fed President Kashkari said the quiet part out loud: There probably won't be any rate cuts in 2024 if inflation continues to move “sideways.”

Today, Fed Governor Bowman came out and said out loud: “Although this is not my baseline forecast, I still see the risk that at a future meeting we may need to raise interest rates further if progress on inflation stalls or even reverses.” .

They are talking about short-term interest rates, not long-term returns. They worry that something big has changed in the economy: that even short-term interest rates of 5.25% to 5.5%, which were supposed to be “restrictive” and were widely expected to push the economy into recession, have changed. It was not restrictive and did not slow the economy.

On the contrary, economic and labor market growth accelerated in 2023, and the labor market has maintained its rapid growth so far in 2024, creating job opportunities at a rate of 3.3 million jobs annually in the first quarter, which is a hot quarter, and hotter than in 2020. 2023. Financial conditions have eased, and markets are in good shape.

So people wonder what kind of interest rate would actually be “constrained” if 5.5% at current inflation rates were not constrained. If inflation on a three-month and six-month basis is 4% or 5%, where should official interest rates be tied?

The three-month core CPI accelerated to 4.2% year-on-year, the highest level since May 2023, and the three-month core services CPI accelerated to 5.6%.

Interest rates are 5.25% to 5.50%. It must be higher than inflation rates to be restrictive; There is widespread agreement on this. But how much higher than that is uncertain.

There are many measures of inflation in the United States. But if we use the three-month measure of core CPI, which was 4.2% in February, neutral interest rates could reach 6.0%, and anything less than that will still be stimulating.

Obviously everyone is just guessing. Inflation has fallen a lot, but is now on the rise again. The path of inflation is highly uncertain, as we have seen. It's possible it could turn around and land again, but that seems unlikely now. Inflation often reveals counterfeiting.

The economy and labor market have been growing at an above-average pace, yet interest rates have been above 5% since May 2023 and more than 4% since December 2022. With this kind of growth, and the inflation we have, they are not constrained.

The bond market is adapting to this scenario and appears to be heading towards the old normal – the normal of 20 or 30 years ago, as we can see in the long-term chart:

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate that very much. Click on the beer and iced tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Register here.

![]()

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25550621/voultar_snes2.jpg)

More Stories

Bitcoin Fees Near Yearly Low as Bitcoin Price Hits $70K

Court ruling worries developers eyeing older Florida condos: NPR

Why Ethereum and BNB Are Ready to Recover as Bullish Rallies Surge