Deep in the ocean, not all ecosystems are built alike.

And as an international team of scientists has now found, the deepest depths are dominated by a certain type of organism. Below a depth of about 4,400 m (14,436 ft), most of the creatures lurking in the dark have smooth, soft bodies. Just above this line are generally hard-shelled molluscs.

Scientists believe that the reason is related to the availability of the minerals that make up the shells. This knowledge can help us protect biodiversity against human activity in these cold, dark, and cool environments.

“The muddy abyssal sea depths were initially considered ‘marine deserts’ when they were first explored several decades ago, due to the extreme conditions of life there – with a lack of food, high pressure and extremely low temperature,” says deep-sea ecologist Erik Simon-Lledó of the UK’s National Oceanography Centre.

“But with the advancement of deep exploration and technology, these ecosystems continue to reveal significant biodiversity, comparable to diversity in shallow water ecosystems, and only found at a much wider spatial spread.”

the abyssal ocean covers more than 60 percent Earth’s surface, but little is known about the life that inhabits it. It’s an environmental bane for humans: crushing stresses, freezing temperatures, and permanent darknessFar from sunlight.

However, technology has improved to the point that we can remotely explore these dark depths, revealing the strange, soft underbelly of the world.

Using deep sea robotics, Simon-Lledó and his team have collected a large database of images from abysmal plain known b Clarion Clipperton ZoneIt stretches 5,000 km (3,107 mi) on the bottom of the Pacific Ocean between Mexico and Kiribati at depths between 3,500 and 6,000 metres.

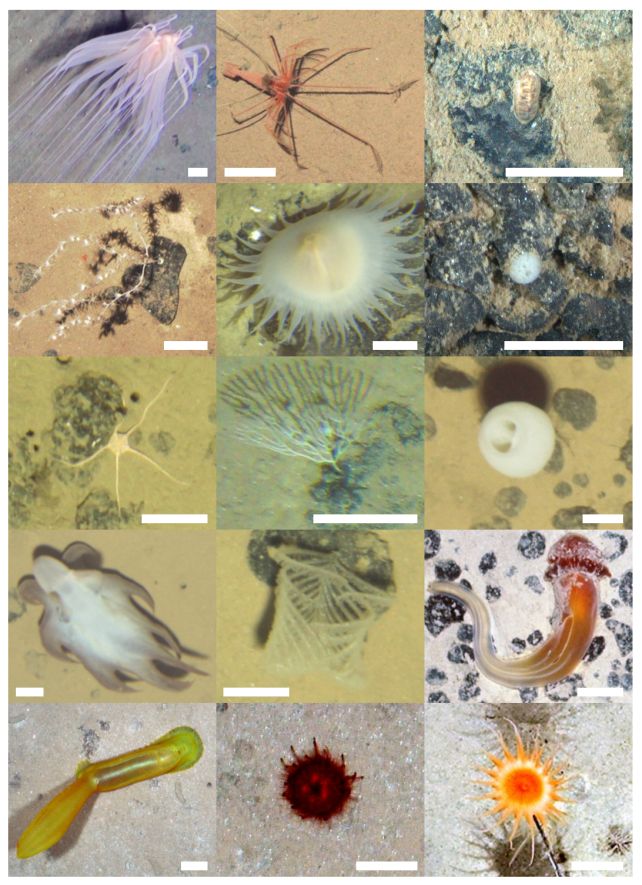

They meticulously cataloged all the animals they could find larger than 10 millimeters in size from these images. They have indexed over 50,000 Abyssal creatures – And they noticed a marked difference in the types of animals found at shallow depths compared to those found in the deepest parts of the area.

“We were surprised to find a deep province clearly dominated by soft anemones and sea cucumbers and an abysmal bottom where suddenly soft corals and brittle stars were everywhere,” says Simon-Ledo.

Molluscs, with their hard shells, did not appear at a depth of less than 4,400 meters, although all kinds of abyssal life lived in a transitional zone between the two regions. The researchers found that this particular depth is likely associated with Depth of carbonate compensation.

Solid shells are formed from Calcium carbonate, which spreads across the ocean from the surface. But below a certain depth, insufficient calcium carbonate remains, which leads to its shortage on the sea floor, To be eaten by hard-shelled animals.

This suggests that there is a delicate balance at play in the biodiversity of the deep ocean, a balance that can easily be disrupted by ocean acidification, climate change, and deep-sea mining, and for which the Clarion-Clipperton Zone is currently being considered.

“Overall, this reflects much higher environmental variability, at multiple scales, than previously expected for benthic assemblages across the northeastern Pacific abyssal sea floor,” the researchers write in their paper.

“This overlooked variability, caused by geochemical and climatic influences, has critical implications for future ecological and macro-environmental research in abyssal communities and for the success of regional-scale conservation strategies that have been implemented to protect biodiversity in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone and possibly in other abyssal regions targeted by deep-sea mining around the world.”

Research published in nature and its evolution.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25550621/voultar_snes2.jpg)

More Stories

Watch a Massive X-Class Solar Explosion From a Sunspot Facing Earth (Video)

New Study Challenges Mantle Oxidation Theory

The theory says that complex life on Earth may be much older than previously thought.