Looking through a powerful microscope, the researchers were shocked to see the impressions left by single-celled plankton, or fossilized nanoplankton, that lived millions of years ago — especially since they were analyzing something else.

“The discovery of ghost fossils was a complete surprise,” said study author Sam Slater, a researcher at the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm.

“We were actually studying fossil pollen from the same rocks. I had never seen this type of fossil preservation before, and the discovery was doubly surprising because the fingerprints are found in abundance from rocks where natural nanofossils are scarce or missing altogether.”

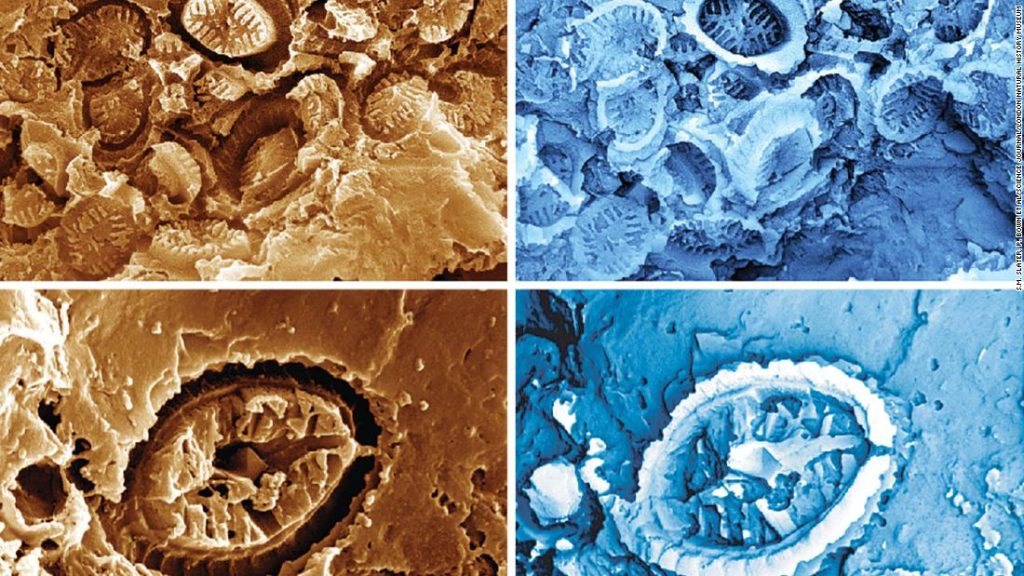

As the researchers examined pollen grains under a scanning electron microscope, Slater said, they spied “tiny pits” on the surface of the pollen. When they zoomed in to see the craters with magnifiers thousands of times, they noticed intricate structures.

Those structures were the impressions left by the exoskeletons of nanoplankton called coccolithophores.

These microscopic plankton are still present today, and they support marine food webs, provide oxygen and store carbon in seafloor sediments. The coccolithophore surrounds its cell with a coccolith, or hard calcareous plate, which can petrify into rocks.

Although small as individuals, they can produce flowers that look like clouds in the ocean that can be seen from space. Once they die, their exoskeletons drift down to the sea floor. When it accumulates, exoskeletons can turn into rocks like chalk.

Ghost fossils arose when seafloor sediments were turned into rock. Layers of mud accumulating on the sea floor compressed the hard sap plates with other organic matter, such as pollen and spores. Over time, the acidic water trapped within the rocky voids dissolved the juices. All that remains is the impression in the stone they once made.

“The preservation of these ghostly nanofossils is really remarkable,” study co-author Paul Bowen, professor of microbiology at University College London, said in a statement.

“Ghost fossils are very small – about five thousandths of a millimeter long, fifteen times narrower than the width of a human hair! – but the details of the original plates are still perfectly visible, pressed against the surfaces of antiquity organic matter, although the plates themselves have melted, Bowen said.

fill a gap

Previous research noted a decline in these fossils during previous global warming events that affected the oceans, leading scientists to believe that plankton may have been negatively affected by ocean acidification and climate change in general.

Ghost fossils tell an entirely different story, providing a record showing that coctophores were abundant in the ocean during three ocean warming events 94 million, 120 million and 183 million years ago through the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods.

“Usually, paleontologists search only for fossils themselves, and if they find none, they often assume that ancient plankton communities have collapsed,” study co-author Fifi Vajda, a professor at the Swedish Museum of Natural History, said in a statement. .

“Ghost fossils show us that sometimes the fossil record plays a trick on us and there are other ways in which these calcareous nanoplankton can be preserved, which must be considered when trying to understand responses to climate change in the past.”

Researchers initially focused on the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event, when volcanoes released an increased amount of carbon dioxide in the southern hemisphere and caused rapid global warming 183 million years ago during the early Jurassic.

Scientists have discovered ghost fossils in the UK, Japan, Germany and New Zealand associated with this event, as well as samples found in Sweden and Italy linked to ocean warming 120 million years and 94 million years ago, respectively.

Understanding ghost fossils can help researchers search for them in other gaps in the fossil record and better understand periods of warming throughout Earth’s history.

dead zones

The plankton weren’t just resilient to high temperatures—they really diversified and thrived, which might not have been a good thing for other species.

Large plankton blooms aren’t a sign that an ecosystem is in trouble, but when blooms die and sink to the sea floor, their decomposition uses oxygen and drains them of the water, potentially creating areas where most species cannot survive.

“Rather than being victims of previous global warming events, our records indicate that plankton dispersal contributed to the expansion of marine dead zones – areas where oxygen levels on the sea floor were too low for most species to survive,” Slater said.

“These conditions, as dead zones expand and plankton proliferate, may become more prevalent across our warming oceans globally,” he added.

Current global warming is happening more quickly than these historical events, and Slater believes this study shows that scientists need a more accurate approach to predicting how different species will respond to global climate change, because not all of them will respond in the same way.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25550621/voultar_snes2.jpg)

More Stories

Watch a Massive X-Class Solar Explosion From a Sunspot Facing Earth (Video)

New Study Challenges Mantle Oxidation Theory

The theory says that complex life on Earth may be much older than previously thought.