The crash of Russia’s Luna-25 spacecraft on the moon on August 19 marked the latest failed attempt by space agency Roscosmos to explore interplanetary space. While the causes of the accident are still being investigated, it is already clear that it resulted from a series of problems plaguing the Russian space program: lack of funding and engineering personnel, dependence on state political interests, and weakness. Western sanctions in the purchase of critical electronic components.

Launching a research probe to the Moon has been a goal of Russian scientists since the 1990s. The first interplanetary mission of the modern Russian state, Mars 96, failed in 1996. As a result, science organizations decided to moderate their ambitions and adopt a seemingly easier goal — landing a probe on the moon.

At that time, Russia’s space program was in a different position than it is today. Although the industry was severely underfunded, it had a highly professional staff who, in Soviet times, organized successful research expeditions to Venus. The Soviet Union had less luck getting to Mars, but that was due to a shortage of Soviet electronics, not a lack of professionalism.

Funding for the project became stable only in 2005, when Roscosmos included it in the federal space program for the period 2005-2015. Subsequently, the project had to be reviewed again and again, primarily due to this lack of funding.

In the first decade of the 21st century, the space program suffered from a financial crisis, and there was constant competition for money between different projects within the industry. Their supporters were called “Martians”—those who wanted to research Mars; “Madmen” – those who prioritized the moon; and “astrophysicists” – who wanted to explore more in deep space. Priority was given to projects that had the support of international partners or that promised ambitious discoveries.

Much has relied on the authority of major lobbies from every denomination. At first, astrophysicists won, and were able to get funds for the Integrated Space Telescope project in cooperation with the European Space Agency.

When it came to exploring the solar system, Roscosmos remained focused on Mars, so the Phobos-Grant project was given preference. The mission promised an even more ambitious feat: recovering soil from Mars’ largest moon, Phobos. The moon has always been peripheral to the interests of the state and has therefore been funded on a residual basis.

The odds of sending a mission to the Moon increased in 2011, when the Spektr-R space telescope was launched in the summer, much to the delight of astrophysicists. But the Phobos-Grunt spacecraft suffered a mechanical failure that winter, fell apart during its return to Earth’s atmosphere. The plans for the lunar module were based on the Phobos-Grunt design. And its failure forced the engineers back to the drawing board. Also at that time, the makeup of the space industry itself was changing dramatically. Experienced scientists were leaving, and younger specialists were taking their place. They needed new ambitious projects with a high degree of risk to gain experience and prestige.

Several factors affected the implementation of the Luna program simultaneously. Chief among them was Russia’s seizure of Crimea in 2014, which prompted the United States Penalties Banning the export of high-tech electronic components to Russia. Many important electronic items had to be refurbished or purchased from new suppliers. One of these devices – the Bius-L inertial navigation unit – could no longer be imported, so it had to be produced locally. Luna-25’s success depends on its correct function when it crashes.

The second difficulty arose again because of the competition between the Martians and astrophysicists. Although funding for space research in Russia improved during the first decade of the 21st century, missions were left to compete for engineering personnel. The production of components for the space program is dominated by the state-owned Lavochkin Association. However, its manufacturing capacity was split between producing parts for weather observation satellites, the Mars mission, and space telescope programs. As these missions were given higher priority, work on Moon-25 was delayed.

Finally, in 2019, the Lavochkin Society completed its part in these projects, leaving more time for the lunar program. Recent launch delays and postponements, first to 2022 and then to 2023, have again been linked to replacement consoles for imports. It would control the spacecraft’s location, speed and distance from the lunar surface.

On August 11, 2023, Luna-25 finally launched from the Vostochny cosmodrome in Russia’s far east. A month earlier, India launched its lunar module, Chandrayaan 3, which was supposed to land relatively close to its Russian counterpart. An undisclosed race was revealed between the two investigations. India had the lead, but its craft was moving on a more conservative path. According to the plan, Chandrayaan-3 was supposed to land two days after the Russian spacecraft landed, on August 23.

In the end, Luna-25 managed to get closer to the Moon than Chandrayaan 3, but by then Russian experts had noted “worrying signs”.

An error occurred during the rover’s first trajectory correction to the moon, requiring a restart of the engines. It has already become clear that the Luna-25 flight was not going according to plan, although this has not been officially announced. Once it began orbiting the moon, nothing stopped scientists from leaving the device for a few days, or even months, so they could study its flaws and try to fix them. Luna-25 was expected to operate on the moon for up to a year, so the station could have remained in orbit for a long time in the event of a malfunction. But if that had happened, India would have overtaken Russia in the race to become the first conqueror of the region around the moon.

In addition, Russia celebrates Flag Day on August 22. The Russian flag was placed on board the Luna 25 spacecraft before its launch – perhaps Roscosmos wanted to publish for the first time a photo of the Russian flag planted on the moon to celebrate the holiday.

The last operation before landing of Luna-25 was to enter a pre-landing orbit above the Moon, at an altitude of between 18 and 100 km. When the engine was started, it took about one and a half times longer than planned. Because of this, the orbit angle dropped to intersection with the surface, and the device crashed on the far side of the moon.

And the consequences of the accident may primarily be manifested in a reduction in funding for future scientific projects in space when Roscosmos formulates a new federal space program for the period 2025-2034. More precisely, this incident, and the damage it caused to the country’s position in this field, could become a suitable reason to reduce research budgets at a time when all the country’s priorities are directed towards the needs of the Ministry of Defense.

Scientific research and exploration of the moon is so alien to the interests of the current Russian government that scientists and officials at Roscosmos will have to work hard to convince officials to give them the necessary funding to continue.

Russia’s next mission to the Moon, Luna 26, is scheduled to launch no later than 2027, and Luna 27 no later than 2028. But those dates may change depending on events on the front line, the economic situation at home, and the status quo. The stability of the Kremlin’s power.

The opinions expressed in the opinion articles do not necessarily reflect the position of The Moscow Times.

“Amateur organizer. Wannabe beer evangelist. General web fan. Certified internet ninja. Avid reader.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25550621/voultar_snes2.jpg)

More Stories

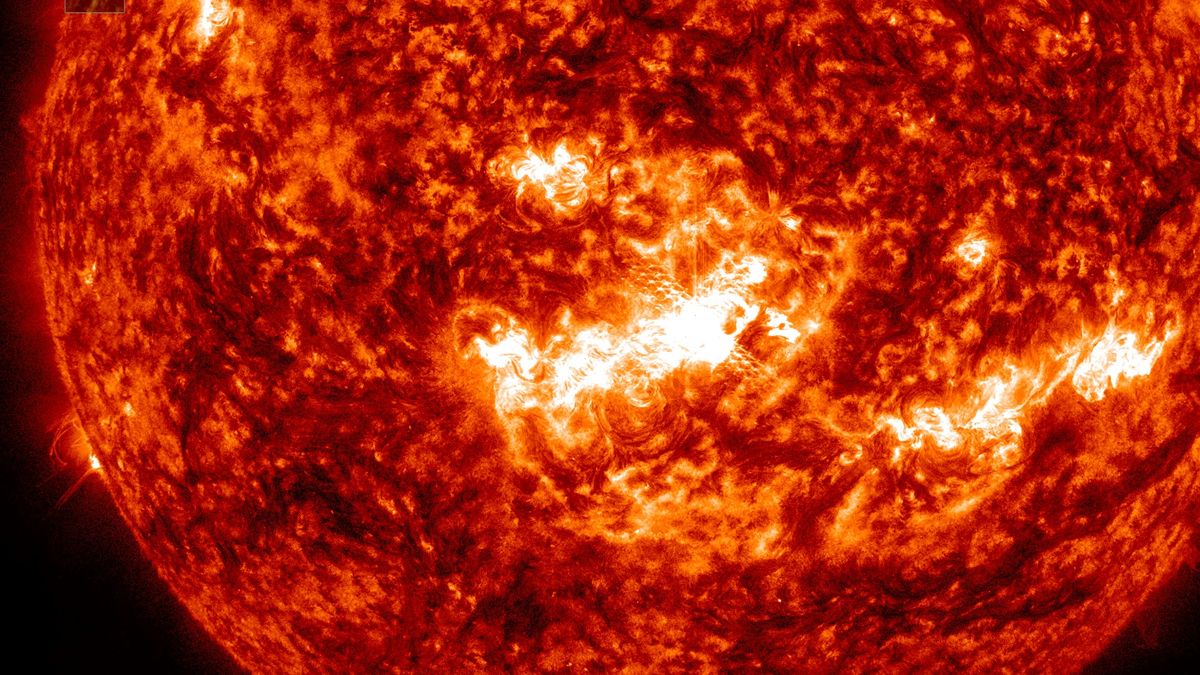

Watch a Massive X-Class Solar Explosion From a Sunspot Facing Earth (Video)

New Study Challenges Mantle Oxidation Theory

The theory says that complex life on Earth may be much older than previously thought.