CNN

—

Scientists have looked back in time to reconstruct the past life of Antarctica's “Doomsday Glacier” – nicknamed because its collapse could cause a catastrophic sea level rise. They found that it began to retreat rapidly in the 1940s, according to a new study that provides an alarming look at future melting ice.

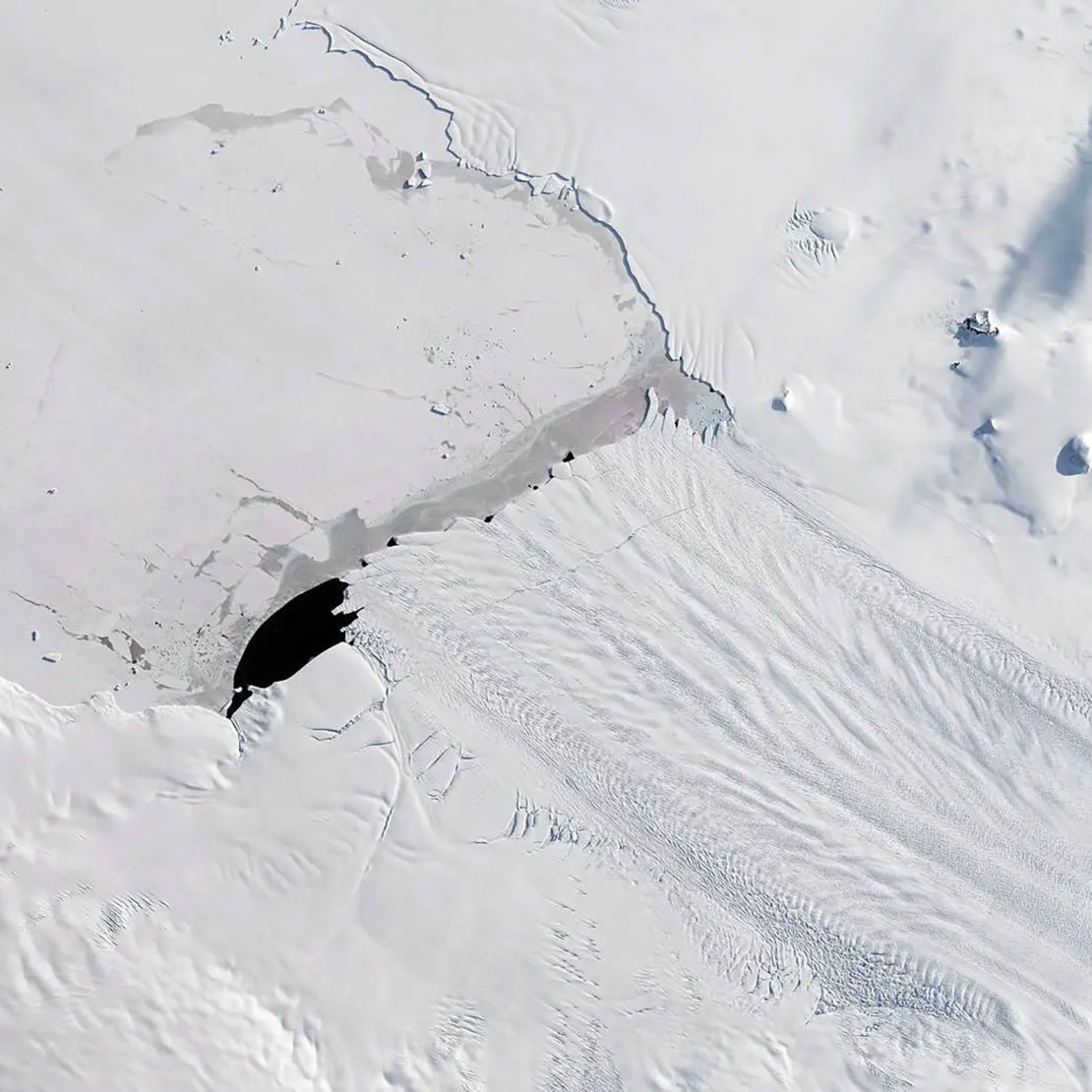

The Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica is the widest in the world and is roughly the size of Florida. Scientists knew it had been losing ice at an accelerating rate since the 1970s, but because satellite data went back only a few decades, they didn't know exactly when the major melting began.

Now there's an answer to that question, according to a study published Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

By analyzing marine sediment cores extracted from beneath the ocean floor, researchers found that the glacier began to retreat significantly in the 1940s, likely due to a very strong El Niño – a natural climate fluctuation that tends to warm impact.

Since then, the glacier has not been able to recover, which may reflect the increasing impact of human-caused global warming, according to the report.

What happens to Thwaites will have global repercussions. The glacier already contributes 4% of Sea levels rise because it dumps billions of tons of ice annually into the ocean. Its complete collapse could raise sea levels by more than two feet.

But they also play a vital role in stabilizing the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, acting like a cork holding back the vast expanse of ice beyond. A Thwaites collapse would undermine the stability of the ice sheet, which contains enough water to raise sea levels At least 10 feetcausing catastrophic global floods.

The study's findings match previous research on the nearby Pine Island Glacier, one of the largest ice streams in Antarctica, which scientists also found began to retreat rapidly in the 1940s.

This makes the research important, said Julia Wilner, an assistant professor of geology at the University of Houston and one of the study's authors. She told CNN that what is happening to Thwaites is not limited to one glacier, but is part of the larger context of a changing climate.

“If both glaciers are retreating at the same time, that's further evidence that they are actually forced into something,” Wilner said.

To build a picture of Thwaites' life over the past nearly 12,000 years, scientists took an icebreaker ship near the edge of the glacier to collect samples of ocean sediments from a range of depths.

These cores provide a historical timeline. Each layer provides information about the ocean and ice dating back thousands of years. By surveying and dating the sediments, scientists were able to determine when the great melting began.

From this information, they believe that Thwaites' retreat was due to an extreme El Niño event that occurred at a time when the glacier was most likely in the process of melting, causing it to lose its balance. “It's like if you were kicked and you were already sick, it would have a much greater impact,” Wilner said.

James Smith, a marine geologist at the British Antarctic Survey and co-author of the study, said the findings are worrying because they suggest that once major changes occur, they will be very difficult to stop.

“Once the ice sheet starts to retreat, it can continue for decades, even if what started doesn't get worse,” he told CNN.

While similar declines have occurred in the past, the ice sheet has recovered and grown again, Smith said. But these glaciers “show no signs of recovery, which likely reflects the increasing impact of human-caused climate change.”

The study confirms and adds details to our understanding of how Thwaites' retreat began, said Ted Scambos, a glaciologist at the University of Colorado Boulder who was not involved in the research.

A system that was already on the verge of instability “took a big hit from a mostly natural event,” Scambos said, referring to El Niño. “Additional events caused by the warming climate trend took things even further and initiated the widespread decline we are seeing today,” he told CNN.

The research shows that if a glacier is in a delicate state, “a single event can push it back so that it is difficult to recover from,” said Martin Troffer, a professor of physics at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

“Humans are changing the climate, and this study shows that small, persistent changes in climate can lead to gradual changes in the condition of glaciers,” said Troffer, who was not involved in the research.

Antarctica is sometimes called the “sleeping giant” because scientists are still trying to understand how vulnerable this isolated icy continent is to humans warming the atmosphere and oceans.

Wilner is a geologist — focusing on the past, not the future — but she said this study provides important and troubling context for what might happen to the ice in this vital part of Antarctica.

It appears that even if the rapid dissolution stimulus ends, this does not mean that the response stops. “So, if the ice is actually retreating today, just because we might stop warming, it may not stop its retreat,” she said.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25550621/voultar_snes2.jpg)

More Stories

Watch a Massive X-Class Solar Explosion From a Sunspot Facing Earth (Video)

New Study Challenges Mantle Oxidation Theory

The theory says that complex life on Earth may be much older than previously thought.