CNN

–

For the first time ever, US scientists at the National Ignition Facility at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California have succeeded in producing a nuclear fusion reaction that has generated a net energy boost, a source familiar with the project has confirmed to CNN.

The US Department of Energy is expected to officially announce the hack on Tuesday.

The result of the experiment will be a huge step in the decades-long quest to unlock an endless source of clean energy that can help end dependence on fossil fuels. Researchers have tried for decades to recreate nuclear fusion – the replica of fusion that powers the sun.

US Department of Energy Jennifer Granholm on Tuesday announced a “major scientific breakthrough,” the Energy Department announced Sunday. The hack was first reported by Financial Times.

Nuclear fusion It occurs when two or more atoms fuse into a larger one, a process that generates a huge amount of energy in the form of heat. Unlike nuclear fission, which supplies electricity around the world, it does not generate long-lived radioactive waste.

Scientists around the world have been slowly making progress toward this breakthrough, using different methods to try to achieve the same goal.

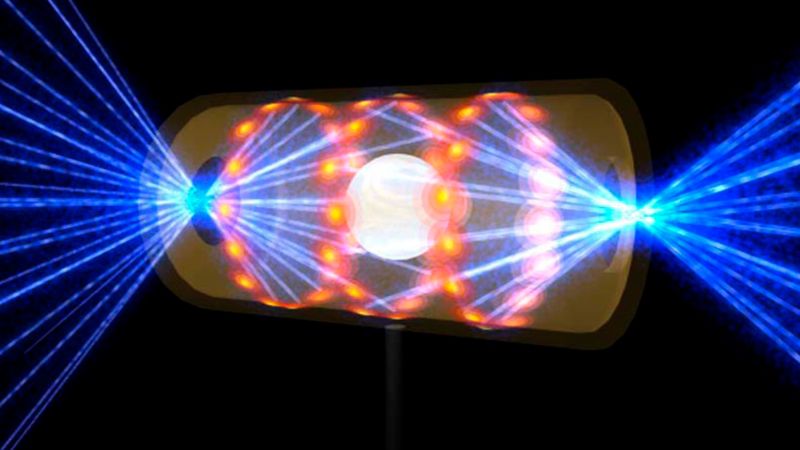

The National Ignition Facility project produces energy from nuclear fusion by what is known as “thermonuclear inertial fusion”. In practice, American scientists fire pellets containing hydrogen fuel in an array of nearly 200 lasers, essentially triggering a series of extremely fast explosions repeated at a rate of 50 times per second.

The energy gathered from the neutrons and alpha particles is extracted as heat, and this heat is key to energy production.

“They contain the fusion reaction by bombarding the outer surface with lasers,” Tony Rolston, a fusion expert from the University of Cambridge’s Department of Engineering, told CNN. “They heat the outside. That creates a shock.”

Although it’s a big deal to get a net energy gain from nuclear fusion, it happens on a much smaller scale than what’s needed to run electrical grids and heat buildings.

“It’s about what it takes to boil 10 kettles of water,” said Jeremy Chittenden, co-director of the Center for Inertial Fusion Studies at Imperial College London. “In order to turn that into a power plant, we need to make bigger energy gains — we need them to be much bigger.”

In the UK, scientists are working with a giant donut-shaped machine fitted with giant magnets called a tokamak to try to get the same result.

The lost mass turns into a huge amount of energy. The temperature of the plasma must reach at least 150 million degrees Celsius, 10 times hotter than the core of the sun. The neutrons able to escape from the plasma then strike a “blanket” lining the walls of the tokamak, transferring their kinetic energy as heat. This heat can then be used to heat water, generate steam and power turbines to generate power.

Last year, scientists working near Oxford were able to generate a record amount of sustainable energy. However, it only lasted 5 seconds.

Whether it’s using magnets or shooting pellets with lasers, the result is ultimately the same: the heat maintained by the process of fusing the atoms together is key to helping produce the energy.

The big challenge of harnessing fusion energy is to keep it going long enough for it to be able to power electric grids and heating systems around the world.

Chittenden and Roulstone tell CNN that scientists around the world must now work to greatly expand the scope of fusion projects, as well as bring down the cost. Getting it commercially viable would take years of research.

“Right now, we spend an inordinate amount of time and money on every experiment we do,” Chittenden said. “We need to bring the cost down by a huge factor.”

Nevertheless, Chittenden called this new chapter in nuclear fusion a “very real and exciting breakthrough moment.”

Roulstone said there’s a lot more work to do to make the merger capable of generating electricity on a commercial scale.

“The counterargument is that this result is miles away from the actual energy gain required to produce electricity,” he said. “So, we can say (it’s) a success for science but far from providing useful energy.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25550621/voultar_snes2.jpg)

More Stories

Bitcoin Fees Near Yearly Low as Bitcoin Price Hits $70K

Court ruling worries developers eyeing older Florida condos: NPR

Why Ethereum and BNB Are Ready to Recover as Bullish Rallies Surge