Credit: Pixabay/CC0 Public Domain

× Close

Credit: Pixabay/CC0 Public Domain

Trace minerals are nutrients, such as zinc, that animals and plants need in small amounts to function properly. Animals generally obtain trace minerals in their diet or through environmental exposure, while plants obtain trace minerals from the soil. If we get too little, we may experience a deficiency, but the opposite may also be true: too many trace minerals can be toxic.

Scientists believe that up to 50% of trace metals found in soil and urban environments may be bound to mineral grain surfaces, making trace metals essentially unavailable for consumption or exposure. Researchers at Washington University in St. Louis wondered why they were where they were.

“When minerals bind trace minerals, we often assume they act like a sponge,” said Jeffrey J. Catalano, professor of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences and director of environmental studies in Arts & Sciences. “But sometimes, they bind trace minerals and don't let them go. That's great when they're contaminants, but bad when they're micronutrients.”

in a study published In the magazine Environmental science and technologyCatalano and Greg Ledingham, Ph.D. One candidate in his lab discovered that a common mineral called goethite—an iron-rich mineral abundant in the soil that covers the Earth—tends to incorporate trace metals into its structure over time, binding the minerals in a way that locks them out of circulation.

The researchers found that the proportion of trace minerals that bind to goethite scales with the size of the ions. Up to 70% of the nickel, the trace metal with the smallest ionic radius in this study, was unrecoverable, while only 8% of the cadmium was irreversibly bound to goethite.

“In the past, to study how trace metals attach and are retained on mineral surfaces, geochemists had to dramatically alter chemical conditions in ways that were not realistic or realistic for real-world systems,” said Ledingham, a graduate fellow at Harvard. McDonnell Space Science Center. “Changing pH, for example, affects how molecules pack together and can affect how minerals bond to the surface.

“We used a new approach called isotope exchange that allowed us to track how metals bind, separate and incorporate iron oxyhydroxides in real time and in conditions representative of real soil and river systems,” he said.

“Our study suggests that iron oxyhydroxide minerals, such as goethite, may serve as a much better sink for trace metals than previously thought,” Catalano said.

Knowing that goethite naturally tends to trap trace metals over time could help scientists better predict how certain pollutants move through the environment, the study authors said. It may also mean that trace mineral nutrients added to farm and garden soil may become less effective after a few months.

The results suggest the environmental impact is mixed: Trapping metals that act as pollutants will clean soil and water supplies, but minerals that act as essential nutrients are also unavailable to plants and other organisms, the researchers said.

more information:

Greg J. Ledingham et al., Irreversible mineral binding to goethite controlled by ion size, Environmental science and technology (2024). doi: 10.1021/acs.est.3c06516

“Amateur organizer. Wannabe beer evangelist. General web fan. Certified internet ninja. Avid reader.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25550621/voultar_snes2.jpg)

More Stories

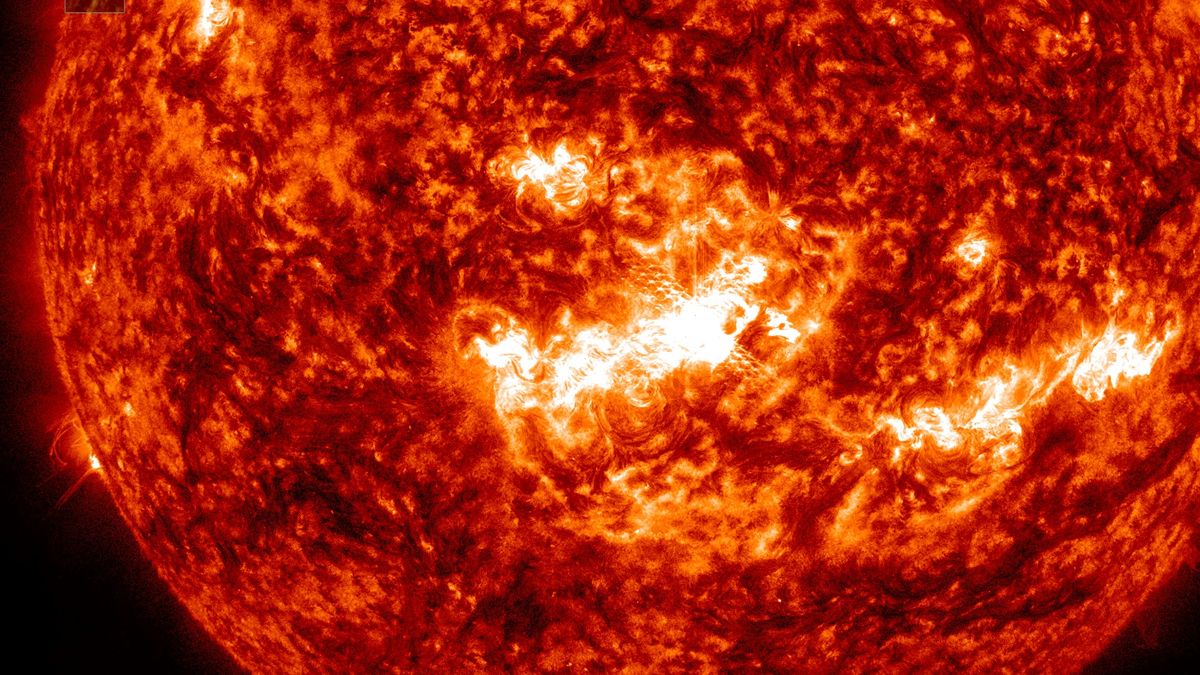

Watch a Massive X-Class Solar Explosion From a Sunspot Facing Earth (Video)

New Study Challenges Mantle Oxidation Theory

The theory says that complex life on Earth may be much older than previously thought.