Written by Martha HenriquesReporter Features@Martha_Rosamund

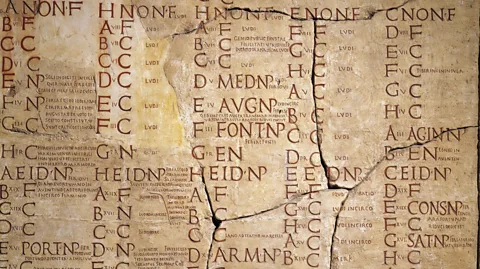

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn order to tame the disorganized Roman calendar, Julius Caesar added months, then deleted them, and invented leap years. But almost the entire grand project was scuttled by a fundamental mathematical error.

It was confusing enough when the harvest celebrations continued into the middle of spring. This was in the first century BC, and according to the ritual, there had to be ripe vegetables ready to eat. But to any farm worker looking around the field, it was clear that there would be many months before harvest.

The problem was the early Roman calendar, which had become so unruly that crucial annual festivals increasingly bore no resemblance to what was happening in the real world.

This irrational system was something Julius Caesar wanted to reform. This was no easy matter: the task was to place the Roman Empire in a calendar consistent with the Earth's rotation on its axis (a day) and its orbit around the sun (a year).

Caesar's answer gave us the longest year in history, added months to the calendar, removed them, linked the calendar to the seasons, and brought us the leap year. It was a major project, and it was almost derailed by a strange flaw in Roman mathematics.

Welcome to the year 46 BC, known as the Year of Confusion.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt may have been a complicated year, but it was not as complicated as it used to be, says Helen Parish, a visiting professor of history at the University of Reading in the United Kingdom.

the Early Roman calendar It was determined by the cycles of the moon and the cycles of the agricultural year. When looking at this calendar with fresh eyes, you may feel some change. There are only 10 months, starting in March in the spring, and the 10th and final month of the year is what we now know as December. Six of those months had 30 days, and four of them had 31 days – Giving a total of 304 days. What about the rest?

“For the two months of the year when there is no work in the field, it doesn’t count,” Parrish says. The sun rises and sets, but according to the early Roman calendar, no day has officially passed. “And this is where the complications start.”

In 731 BC, the second king of Rome, Numa Pompilius, I decided to improve the calendar by introducing additional months to cover that winter period. “Because what good is a calendar that only covers part of the year?” The parish says. Pompilius's answer was to add 51 days to the calendar, resulting in what we now call January and February. This extension brought the calendar year to 355 days.

If 355 days seemed like an odd number for Pompilius to aim for, that was intentional. The number takes its reference from the lunar year (12 lunar months). It is 354 days. However, “because of Roman superstitions about even numbers, an extra day is added to make the number 355,” Parrish says.

In this system, the months are arranged so that they all have an odd number of days, except for February, which has 28 days. “This is therefore considered an unlucky time and a time of social, cultural and political cleansing,” says Parrish. “So that's the point at which you try to clear the slate.”

It's good progress, Parrish says, but it's still about 11 days away from the 365-day-and-a-bit solar year. “Even with this improved calendar from Pompilius, it is very easy for the calendar to get out of sync with the seasons.”

By around 200 BC, things had gotten bad enough that a near-total solar eclipse was observed in Rome on what we now consider to be March 14, but was recorded as having occurred on July 11.

Because the calendar was at this point “catastrophically wrong,” Parrish says, the emperor and the priests in Rome resorted to inserting One more month, Mercedoniuson an ad hoc basis to try to reorganize the calendar to fit the seasons.

This didn't work out very well. There was a tendency to add Mercedonius when favored public officials were in power, for example, rather than strictly aligning the calendar with the seasons.

complained the classical writer and historian Suetonius “The neglect of the popes has long led to turmoil [the calendar]By their privilege of adding months or days of enjoyment, the harvest festivals came neither in summer nor in fall.”

Which brings us back to Julius Caesar. 46 BC had already planned for Mercedonius, but Caesar's advisor Sosigenes, an astronomer from AlexandriaOn the Mediterranean coast of Egypt, he said that Mercedonius would not be enough this time.

On the advice of Sosigenes, Caesar added two more unprecedented months to the year 46 BC, one of 33 days and the other of 34 days, to bring the calendar into line with the sun. These additions made the year the longest in history at 445 days and 15 months.

After 46 BC, the New Months and Mercedonius and the practice of intercalated months as a whole were abandoned, because if all was well, there would be no need for them.

“We're back to a calendar that looks more like the calendar we know,” Parrish says. “Excellent! This sounds refreshingly familiar.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesUnfortunately, getting the calendar aligned with the sun is one thing, but keeping it that way is another. The problem arises from the inconvenient fact that there are not a good number of days (Earth's revolutions) in a year (Earth's orbits around the Sun).

“This is where the whole problem starts,” says Daniel Brown, an astronomer at Nottingham Trent University in the United Kingdom. The number of revolutions of the Earth in its journey around the Sun is About 365.2421897…and he goes on.

This means that the land fits barely An additional quarter turn every time you make a full revolution around the sun. So adding an extra day every four years — in February — would help fix the mismatch, Sosigenes calculates.

This would have worked well, at least for a while, if not for the problem of the unique way the Romans counted years.

“They look at the years and count them: one, two, three, four,” Parrish says. “Then they start counting again at four – so they count four, five, six, seven. Then they start at seven – so seven, eight, nine, 10. So they mistakenly double-count one of those years at a time. “It takes a long time to realize that the slide is starting to happen.”

This was corrected during the reign of Augustus Leap years occurred every four years instead of every three years, and thus the Julian calendar was on its way. “Julius Caesar is getting close to where the calendar should be,” Parrish says.

This might have been the only calendar needed for this task, if the Earth did in fact make an additional quarter turn each year. But it's a bit short – at about 11 minutes.

“This means we are still slowly but surely out of sync,” says Brown.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe solution came much later In 1582 when Pope Gregory made further modifications.

“That's what was then corrected in order to fix the Gregorian calendar — taking note of that and adjusting that calendar a little bit, making sure that not only every four years, but then every 100 years they make sure they cross that rule,” Brown says. . “But then they noticed that this doesn't quite match, I overcompensated. So, don't miss it every 400 years.”

This is why, for example, the year 2000 was a leap year: because it is divisible by 100 and 400.

“It all sounds really neat and tidy,” Parrish says, but this is where politics begin to shape the course of time. “It is a calendar carried out by papal decree, and in fact has no authority outside the Church and outside the care of the Bishop of Rome.”

Parrish says there were people who complained that the pope actually stole 10 or 11 days of their time by adjusting the calendar. However, over the centuries, more and more countries adopted the Gregorian calendar. “But it's nice that they don't all do it at the same time,” Parrish says. “You arranged the calendar, but now you have calendars in different countries that operate on completely different models.”

Read more about People who live in multiple timelines.

Because of this discrepancy, “you can have a more bizarre situation where a reply written in England to a letter arriving from Spain can look as if it was sent before the first letter arrived from Spain,” Parrish says. “Because England is ahead of Spain on the calendar.”

Once the Gregorian calendar was widely adopted and internationally synchronized, it had several thousand years of accuracy. But it's still not perfect.

In fact, around the middle of the 56th century, “someone will scratch their head and say, ‘Wait a minute, it should be Monday, but it actually looks like Tuesday,’” Parrish says. “I think that's probably a margin of error that we'll ultimately accept.”

Until Monday (or Tuesday), the Gregorian calendar has given us at least some time.

—

If you liked this story Subscribe to the Essential List newsletter – A handpicked selection of unmissable features, videos and news delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Join 1 million Future fans by liking us FacebookOr follow us Twitter or Instagram.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25550621/voultar_snes2.jpg)

More Stories

Watch a Massive X-Class Solar Explosion From a Sunspot Facing Earth (Video)

New Study Challenges Mantle Oxidation Theory

The theory says that complex life on Earth may be much older than previously thought.