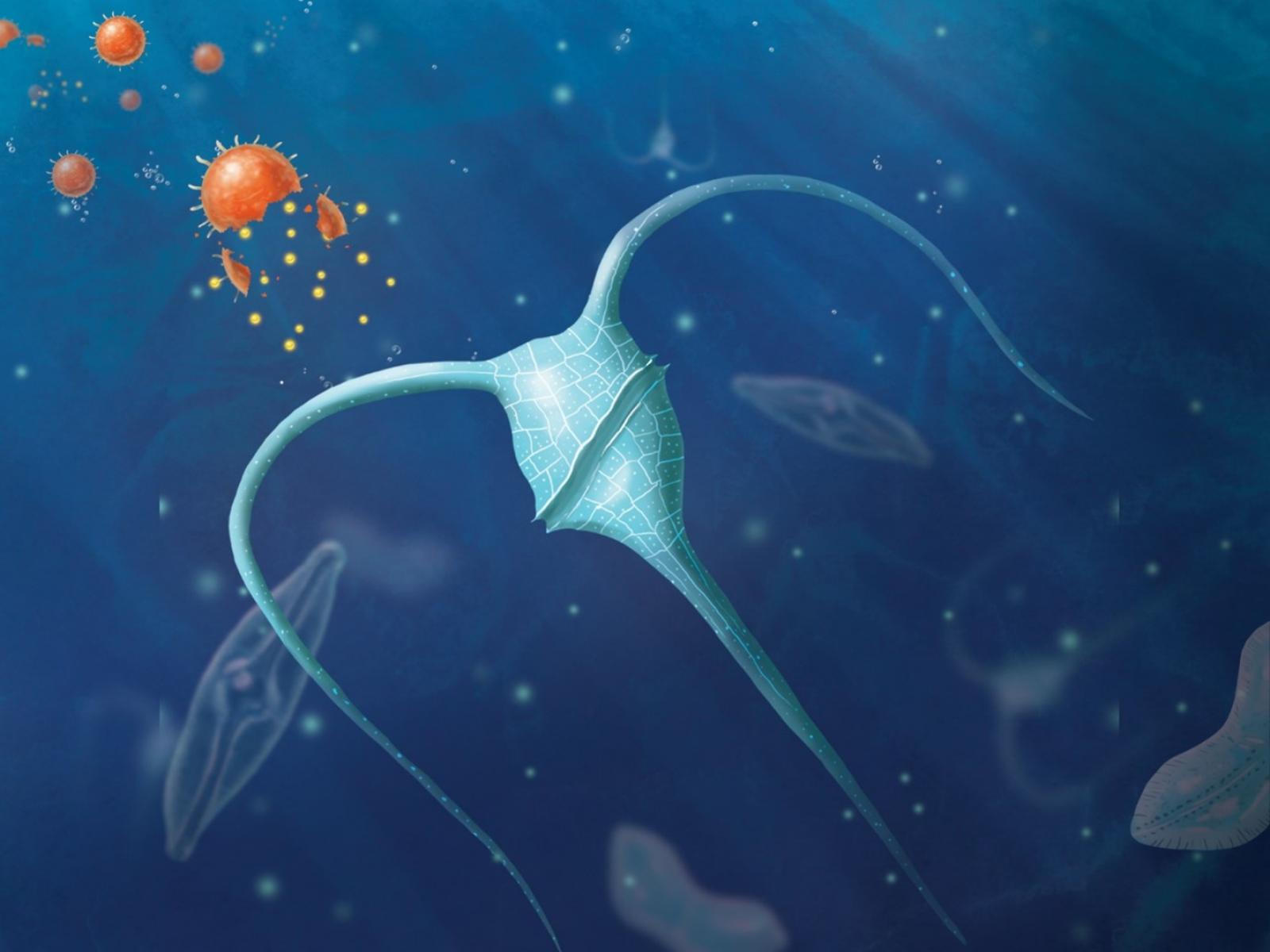

Seeding the oceans with nano-fertilizers could create a big, much-needed carbon sink. Credit: Illustration by Stephanie King | Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

Iron-based fertilizers in the form of nanoparticles have the potential to store excess carbon dioxide in the ocean.

An international team of researchers led by Michael Hochela of Pacific Northwest National Laboratory It is suggested that the use of microorganisms could be a solution to meet the urgent need to remove excess carbon dioxide from the Earth’s environment.

The team conducted an analysis published in the journal Nature’s Nanotechnologyon the possibility of sowing seeds for the oceans with iron-rich engineered fertilizer particles near ocean plankton, microscopic plants critical to the ocean ecosystem, to enhance growth and uptake of carbon dioxide by phytoplankton.

“The idea is to augment existing processes,” said Hochella, a lab fellow at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. Humans have been fertilizing the land to grow crops for centuries. We can learn to fertilize the oceans responsibly.”

Michael Hochela is an internationally recognized environmental geochemist. Credit: Virginia Tech Photographic Services

In nature, nutrients from land reach the oceans through rivers and blow up dust to fertilize plankton. The research team proposes taking this natural process a step further to help remove excess carbon dioxide from the ocean. They have studied evidence that adding specific combinations of carefully designed materials can effectively fertilize the oceans, encouraging phytoplankton to act as a carbon sink. Living organisms will absorb carbon in large quantities. Then, when they die, they will sink to the depths of the ocean, taking the excess carbon with them. Scientists say this proposed fertilization would simply speed up a natural process that is already safely sequestering carbon in a form that could remove it from the atmosphere for thousands of years.

“At this point, time is of the essence,” Hochela said. “To combat rising temperatures, we must reduce carbon dioxide levels on a global scale. Considering all of our options, including using the oceans as a carbon dioxide sink, gives us the best chance of cooling the planet.”

Extract insights from the literature

In their analysis, the researchers argued that engineered nanoparticles offer several attractive features. Highly controllable and specially designed for different ocean environments. Surface coatings can help particles stick to plankton. Some particles also have light-absorbing properties, allowing plankton to consume and use more carbon dioxide. The general approach can also be tuned to meet the needs of specific ocean environments. For example, one area might benefit more from iron-based particles, while silicon-based particles might be more effective in others, they say.

The researchers’ analysis of 123 published studies showed that several non-toxic mineral oxygen substances can safely promote plankton growth. They argue that the stability, abundance of land, and ease of creation of these materials make them viable options as plankton fertilizers.

The team also analyzed the cost of creating and distributing different molecules. While the process will be much more expensive than adding non-engineered materials, it will also be significantly more efficient.

Reference: “Potential Use of Engineered Nanoparticles in Ocean Fertilization for Large-Scale Removal of Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide” by Peyman Babakhani, Tannabon Vinrat, Mohamed Balousha, Colaba Suratana, Carolyn L. Peacock, and Benjamin S. Twining, Michael F. Hochela Jr. Nov. 28, 2022, Available here. Nature’s Nanotechnology.

DOI: 10.1038/s41565-022-01226-w

In addition to Hochella, the team included researchers from England, Thailand, and several US-based research institutions. The study was funded by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Research and Innovation Program Horizon 2020.

“Amateur organizer. Wannabe beer evangelist. General web fan. Certified internet ninja. Avid reader.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25550621/voultar_snes2.jpg)

More Stories

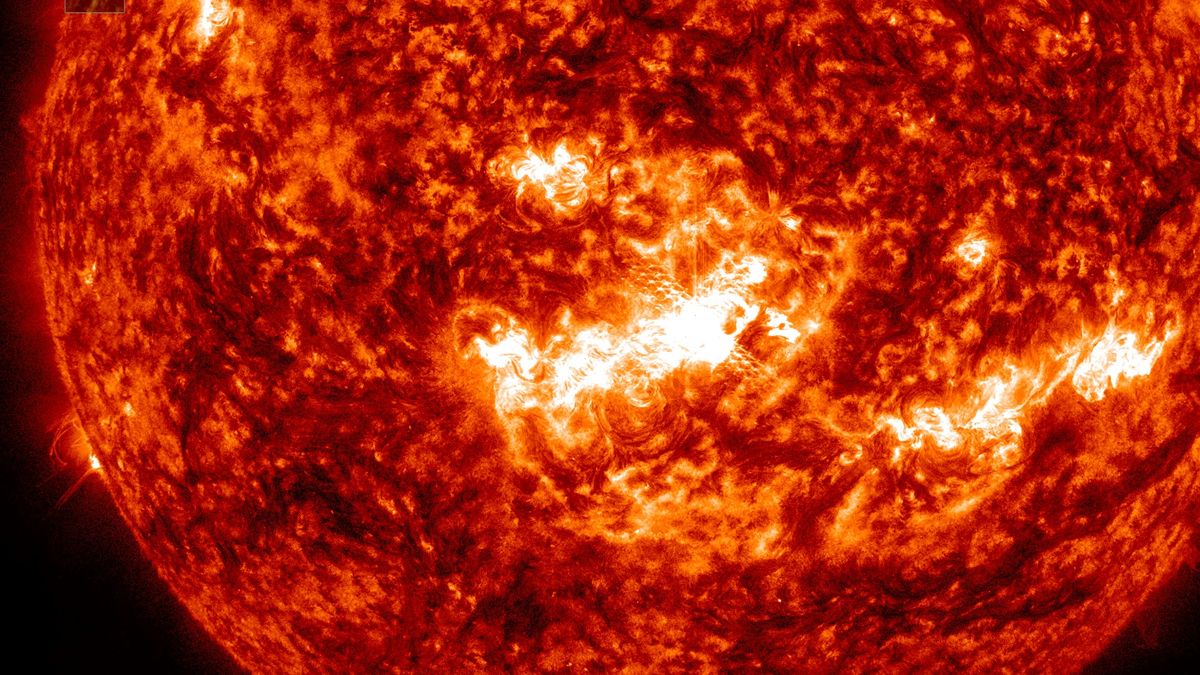

Watch a Massive X-Class Solar Explosion From a Sunspot Facing Earth (Video)

New Study Challenges Mantle Oxidation Theory

The theory says that complex life on Earth may be much older than previously thought.