Penguin Random House

Let me start with TLDR to A city on Mars. It’s basically 400 pages of “well, actually…” but without giving away, there’s a fair amount of humor and plenty of detail. Kelly and Zach Weinersmith started from a position of being space settlement enthusiasts. They thought they would write a lighthearted book about how wonderful everything would be on Mars or the Moon or on a space station. Unfortunately for the Weinersmith family, they’re already asking questions like, “How exactly could this work?” Aside from the rockets (ie, the space access part), the answers were mostly optimistic hand-waving mixed with the kind of apparent New Destiny ideology that might have given Andrew Jackson pause.

The Weiner Smiths begins with human biology and psychology, then passes through technology, law, and population survival, and ends with a kind of call to action. Under each of these sections, the Weiner-Smiths ask questions like: Can we thrive in space? Reproduce in space? Creating habitats in space? The tour through all the unknown things in reality is shocking. No one got pregnant in microgravity, and no embryos developed in microgravity, so we simply don’t know if there’s a problem. Astronauts suffer from bone and muscle loss, and no one knows how this works in the long term. More importantly, do we really want to figure this out by sending a few thousand people to Mars and hoping everything works out?

Then there are the problems of building the house and doing all the recycling. I was shocked to learn that no one really knows how to build a long-term habitable settlement on either the Moon or Mars. Yes, there are a lot of hand-cured ideas about lava tubes and rock armor. But the details are just there…not there. It reminds me of the dark days of Europe when it established colonies on other people’s lands. The stories about how unprepared the settlers were are sad, funny, and hilarious Iterative. And now we know we’re planning at least one more sequel.

Even space law falls under Weinsmith’s microscope. I certainly wasn’t aware of the extent of the law regarding space. But it exists and has a lot to say about what you can and can’t do in space. The Weinersmiths discovered that most space colonization enthusiasts believed, one way or another, that these laws wouldn’t apply to them, or that there were some loophole they could exploit. Worse still, they seem to believe that such exploitation will be free of consequences. It is clear that nuclear-weapon states will not react negatively to the claim of large amounts of space by ordinary citizens.

The Weinersmiths treat all their experts with kindness. But frankly, reading between the lines, there is a thick streak of libertarianism running through the space settlement community. From the point of view of these experts, they need a really big telescope to see reality. For example, it is assumed that space will end scarcity… However, any habitat in space would naturally only have one source of food, water, and, more pressingly, oxygen, creating (and perhaps artificial) scarcity. The idea seems to be that everyone will go into space for profit, except for the necessities of life, where we will all care and share. The magical thinking becomes clearer when you realize that it is believed that confronting the vastness of space will make humanity extremely altruistic, while still being a good capitalist. I have doubts that this philosophy will work well for anyone involved.

In a more realistic view of how societies function when there is only one source of vital life elements, the Weinersmiths draw on experiences (both positive and negative) of company towns. It wasn’t all bad: some company cities were extremely well-run and fair, while others could be designated as shrines to dictatorships. There’s no reason, Al Weinersmith says, to think we won’t see the same thing in space, with the added benefit of not being able to escape company cities.

Even the idea that other resources, such as ores, will not be scarce is overly optimistic. No one knows if you can make a profit from asteroid mining. The moon holds nothing of value at all. And do you really want to create a bunch of hungry, disgruntled miners who are also capable of hurling very large rocks at the ground?

A city on Mars It ends with a kind of call to action. The point is that we have a small space station, and we have the ability to build a lot of experimental facilities on Earth where we can investigate some practical problems. Let’s master biology and engineering before we send humans to Mars. As we work on the technology, the law must be clarified so that if (or when) we settle somewhere else, we do so in a way that does not start a war between angry nations with nuclear weapons.

I think the point is that A city on Mars What we find is that the only clear evidence of how space affects humans is strongly weighted against Going. This balance can be changed by doing the work to discover the answers to some of the questions posed in the book. However, it seems ethically questionable to fire a group of people to get those answers. So, maybe do the work beforehand?

“Amateur organizer. Wannabe beer evangelist. General web fan. Certified internet ninja. Avid reader.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25550621/voultar_snes2.jpg)

More Stories

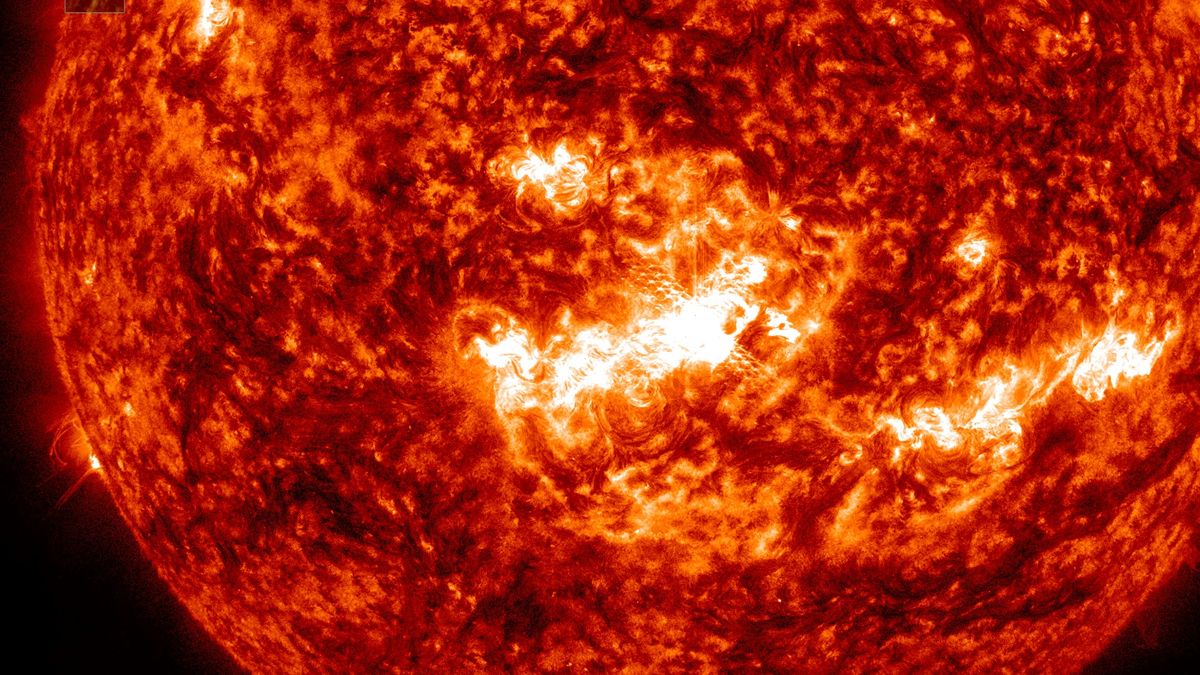

Watch a Massive X-Class Solar Explosion From a Sunspot Facing Earth (Video)

New Study Challenges Mantle Oxidation Theory

The theory says that complex life on Earth may be much older than previously thought.