Recent research on the inner ear structures of the fossil ape Lufengpithecus provides new evidence for the evolutionary steps toward human bipedalism, revealing the important roles of the inner ear and climate change in this evolutionary journey. Reconstructing locomotor behavior and paleoecology of Lufengpithecus. Credit: Illustration by Xiaocong Guo; Image courtesy of Shijun Ni, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences

The inner ear of a fossilized ape, dating back 6 million years, sheds light on the evolution of human locomotion

Humans and our closest living relatives, the apes, exhibit an extraordinary variety of locomotion methods, from walking on two legs to climbing trees and walking on all fours.

While scientists have long been fascinated by the question of how human posture and locomotion evolved from a quadrupedal ancestor, neither previous studies nor fossil records have allowed the reconstruction of a clear and definitive history of the early evolutionary stages that led to human bipedalism.

However, a new study, which focuses on recently discovered evidence from 6-million-year-old fossil ape skulls, LovingbeticusProvides important clues about the origins of bipedal locomotion thanks to a new method: analysis of the bony inner ear region using 3D CT.

“The semicircular canals, located in the skull between our brains and the outer ear, are essential for providing our sense of balance and position when we move, and they also provide an essential element of our movement that most people probably don't realize,” he explains. Yinan Zhang, a doctoral student at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (IVPP) and lead author of the paper, which appears in the journal innovation. “The size and shape of the semicircular canals are related to how mammals, including apes and humans, move around their environment. Using modern imaging techniques, we were able to visualize the internal structure of fossil skulls and study the anatomical details of the semicircular canals to reveal how extinct mammals moved.”

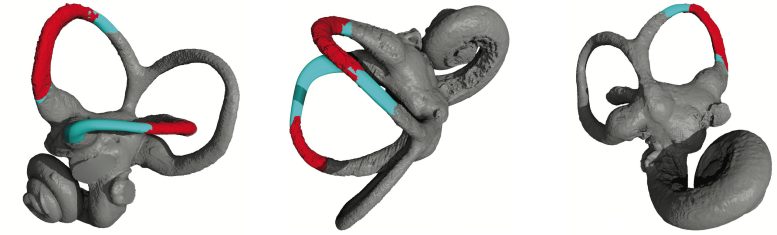

Three different views of the reconstructed inner ear of Lovingpiticus. Credit: Image provided by Yinan Zhang, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences

Evolutionary steps for bipedalism

Adds Terry Harrison, A. “Our study suggests a three-step evolution of human bipedal locomotion.” New york university An anthropologist and one of the paper's co-authors. “First, the first apes moved in the trees in a style that was very similar in aspects to the way gibbons in Asia move today. Second, the last common ancestor of apes and humans was similar in its locomotor repertoire Lovingpithecus, using a combination of climbing and climbing, forelimb suspension, arboreal bipedalism, and ground walking. From this vast locomotor repertoire of ancestors, human bipedal locomotion evolved.

Most studies on the evolution of ape locomotion have focused on comparisons of the bones of the limbs, shoulders, pelvis, and spine and how they relate to the different types of locomotor behaviors seen in living apes and humans. However, the diversity of locomotor behaviors in living apes and the incompleteness of the fossil record have hampered the development of a clear picture of the origins of bipedalism in humans.

Technological advances in fossil examination

Skulls Lovingpithecus— which was originally discovered in China's Yunnan province in the early 1980s — gave scientists the opportunity to address unanswered questions about the evolution of movement in new ways. However, extreme compression and distortion of the skulls obscured the bony ear region and led previous researchers to believe that the delicate semicircular canals were not preserved.

To better explore this area, Zhang, Ni, and Harrison, along with other researchers at IVPP and the Yunnan Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology (YICRA), used 3D scanning techniques to illuminate these parts of the skulls to create virtual reconstructions. From the bony canals of the inner ear. They then compared these scans with those collected from living apes, other fossils, and humans from Asia, Europe, and Africa.

“Our analyzes show that early apes shared a locomotor repertoire that was the ancestor of bipedal humans,” explains IVPP professor Shijun Ni, who led the project. “The inner ear appears to provide a unique record of the evolutionary history of ape movement, providing an invaluable alternative for studying the postcranial skeleton.”

“Most fossil apes and their inferred ancestors are intermediate in locomotor status between gibbons and African apes,” Nee adds. Later, the human lineage diverged from the great apes by acquiring the ability to walk on two legs, as seen in… australopithecus, An early human relative from Africa.”

By studying the rate of evolutionary change in the bony labyrinth, the international team suggested that climate change may have been an important environmental driver in promoting locomotor diversity in apes and humans.

“Colder global temperatures, associated with the buildup of ice sheets in the Northern Hemisphere about 3.2 million years ago, correspond to a slight increase in the rate of change in the bony labyrinth, and this may indicate a rapid increase in the pace of ape-like movement and human locomotor evolution,” he explains. Harrison.

Reference: “The inner ear of Lufengpithecus provides evidence for a shared motor repertoire underlying human bipedalism” by Yinan Zhang, Xijun Ni, Qiang Li, Thomas Stidham, Dan Lu, Feng Gao, Chi Zhang, and Terry Harrison, 14 February 2024, Innovation.

doi: 10.1016/j.xinn.2024.100580

“Amateur organizer. Wannabe beer evangelist. General web fan. Certified internet ninja. Avid reader.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25550621/voultar_snes2.jpg)

More Stories

Watch a Massive X-Class Solar Explosion From a Sunspot Facing Earth (Video)

New Study Challenges Mantle Oxidation Theory

The theory says that complex life on Earth may be much older than previously thought.