There is a consensus among America’s leading astronomers that NASA’s next wave of great observatories should take advantage of the game-changing lifting capabilities provided by giant new rockets like SpaceX’s Starship.

A follow-up launch of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) on the spacecraft, for example, could free the mission from cumbersome constraints related to mass and size, which usually lead to increased complexity and cost, a panel of three astronomers said. He recently stated this to the National Academies Committee for Astronomy and Astrophysics.

“Having greater mass and volume capability, at lower cost, expands the design space,” said Charles Lawrence, chief scientist for astronomy and physics at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “We want to take advantage of that.”

Lawrence’s presentation addressed the impact of large, new launch vehicles on future astronomy missions. The presentation was made last week alongside Martin Elvis, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, and Sarah Seager, an astrophysicist and planetary scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Lawrence, Elvis and Seeger composed A paper earlier this year in the journal Physics Today Discuss this topic.

It is widely recognized that the ability of a spacecraft to lift more than 100 metric tons into space, at a fraction of the cost per kilogram of existing rockets, would change the way the broader space industry operates. The spacecraft is 9 meters in diameter (8 meters of diameter can be used for payload) which is nearly twice the width of the payload volume on any existing rocket.

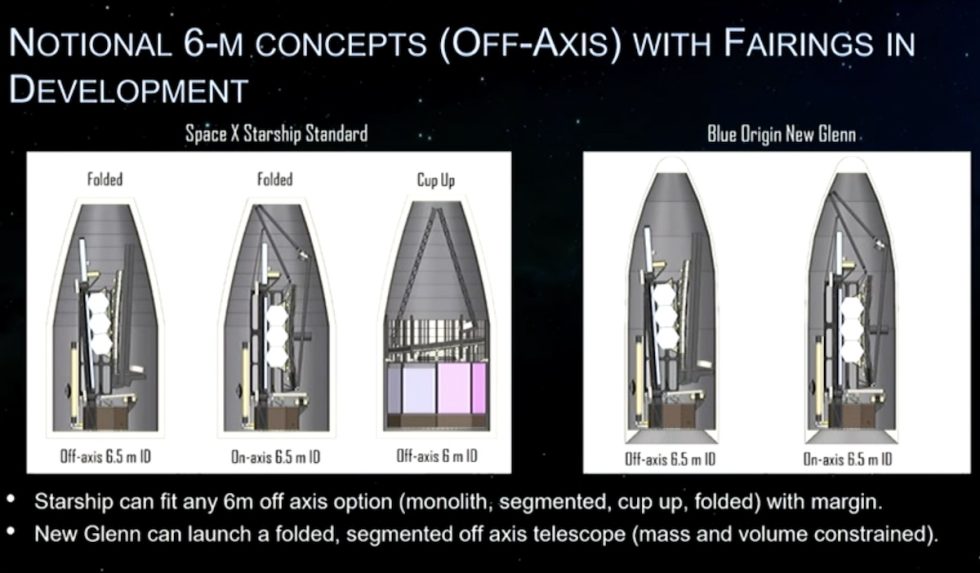

But astronomers are getting serious about planning rockets like Starship, or Blue Origin’s New Glenn with a slightly smaller 7-meter payload, to be available to lift the next generation of large space telescopes.

Big telescopes on big launchers

In 2021, the National Academies Issue a review once every decade Astronomy and astrophysics are a top priority for the American science community. In this survey, known as Astro2020, a distinguished panel of scientists laid out a roadmap for NASA to spend the better part of the 2020s developing technologies and designs for the next series of “great observatories” that will follow the likes of Hubble and Chandra. The James Webb and Romanian Space Telescope is scheduled to launch in 2027.

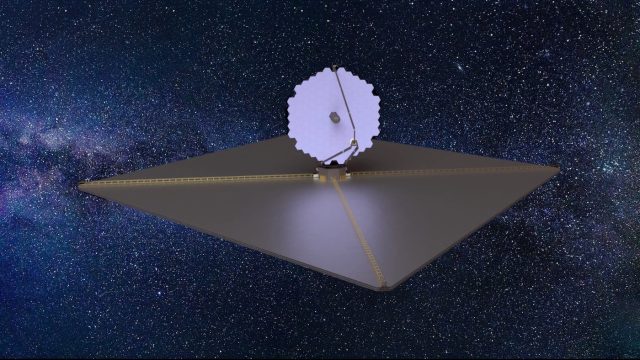

NASA’s policy is to follow the recommendations of the scientific community wherever possible. It is believed that sometime towards the end of the decade, NASA should be ready to officially begin development of these new telescopes. First would be a large telescope called the Habitable Worlds Observatory, which is comparable in size to the Webb telescope with a primary mirror about 6 meters (20 feet) wide and a coronagraph or star shadow to block starlight, allowing direct observations of planets around other planets. Stars, or exoplanets. This is a capability not available on Webb.

The Habitable Worlds Observatory, which has sensitivity to light in the infrared, visible and ultraviolet wavelengths, will be tasked with monitoring Earth-like exoplanets for worlds with the makeup that supports life. Later, NASA should launch similar ambitious far-infrared and X-ray telescopes to study the formation of stars, black holes and galaxies, which scientists have recommended in 2021.

These big new multi-billion dollar missions won’t start launching until the 2040s. This is a “blocking timeline,” Elvis and his colleagues wrote in their paper published earlier this year. “Today’s newly minted Ph.D.s will be barely a decade away from retirement by the time the first observatories are launched.”

NASA doesn’t have the budget to launch them anytime soon, and new telescopes require innovations in optics, detectors, and materials to make them feasible.

Scientists said the arrival of new large rockets may reduce some of these technological hurdles. Ultimately, it could lead to simplified designs, lower costs and perhaps shorten the time needed to develop and build the next great observatories. Maybe they don’t have to wait until the 2040s to launch it. These are important factors when preliminary estimates from the National Academies indicate that the Observatory of Habitable Worlds will cost about $11 billion.

“Designs are very constrained by the launchers, the size and mass available for the orbit you want, and this inevitably increases complexity and cost,” Ilves said.

In the next few years, engineers working on initial designs for these new telescopes must reevaluate their assumptions about the types of rockets that will be available to launch missions into space, Elvis said.

“We propose to conduct studies on all three Astro2020 flagships, their payloads and spacecraft, in the new Starship model, or any large launch model, to take advantage of the open design space,” Elvis said last week.

“The big questions are: Are the significant cost savings we have identified really reasonable and, as a result, can Astro2020 be accelerated?” he added.

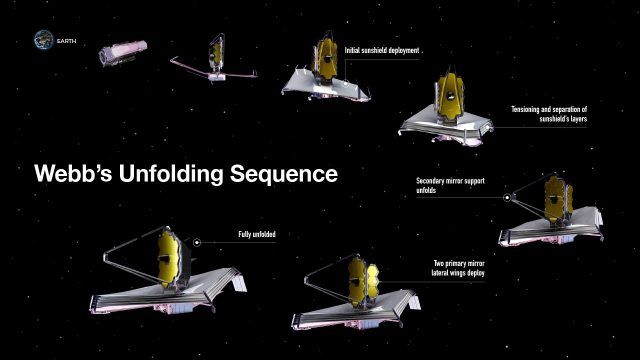

The tyranny of the missile

To illustrate the limitations imposed by the rocket’s capability, let’s return to the James Webb Space Telescope. Webb had to fit within the nearly 5-meter-diameter payload fairing of the Ariane 5 rocket, which had the largest payload envelope of any launch vehicle available when engineers were first designing Webb. This meant that the telescope’s 18 individual primary mirror segments had to be folded, and the designers created a five-layer tennis court-sized sunshade made of flimsy but effective insulation to block the sun’s heat and light from the telescope. It all had to come together to allow Webb to be within the confines of its rocket when it launches in 2021.

With a larger rocket like Starship or New Glenn, a future telescope could use a homogeneous mirror, eliminating the need for segmented mirrors. There are scientific arguments to suggest that segmented mirrors may be better for some applications, but the jury is still out. Also, instead of needing a complex deployable sunshade that would be prone to failure, engineers could install a larger, rigid canopy that wrapped around the entire telescope.

Scientists said that if launched on a massive rocket like Starship, the telescope’s mirrors could be thicker and heavier, meaning they would be easier to manufacture and polish. A heavier rocket could allow spacecraft designers to add larger solar panels for additional power. The extra power could allow the spacecraft to use cheaper electronics with more redundancy, Elvis said.

“One of the biggest lessons learned from the James Webb Space Telescope was the importance of understanding rockets upfront and in detail,” said Lee Feinberg, director of optics at Webb and co-leader of the Technical Evaluation Group studying the Observatory of Habitable Worlds. The key points here are that we want flexibility. “We are more than 20 years away from the mission.”

Who knows what missiles will fly in the 2040s? For the Roman Space Telescope, scheduled to launch a few years from now, NASA officials thought they would have a choice between several rockets. It turns out that new rockets, like United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan and Blue Origin’s New Glenn, weren’t ready when NASA needed to choose a launch contractor. Hypothetically, the contract went to SpaceX to launch on a Falcon Heavy rocket.

“It really highlights the importance of flexibility in rockets,” said Feinberg, an engineer at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. He recently met with SpaceX and Blue Origin. “Our view now is that New Glenn and Starship look promising,” he said.

There are other new missiles. NASA’s Space Launch System is too expensive to even consider. “ULA’s new Vulcan doesn’t have a much larger fairing, so we didn’t even think about that,” Elvis said.

Is spacecraft the solution?

Studies have shown that the spacecraft, with its wider diameter, could accommodate a range of telescope designs, such as the one under consideration for the Habitable Worlds Observatory. The spacecraft can launch the observatory, with its approximately 6-meter primary mirror, folded or unfolded, on its side, or pointing upwards.

“What we found is that with Starship, you really have a lot of flexibility,” Feinberg said at a National Academies committee meeting last week.

Of course, the Starship and New Glenn spacecraft have not yet reached orbit, and they still have several flights to go to become eligible to launch NASA’s main mission. But SpaceX and Blue Origin have two decades to prove the reliability of their new rockets before NASA gets one of its fancy new onboard observatories ready for launch.

“By the time our first great observatory is launched, the spacecraft will have launched several times and have a record that you can judge by,” Seager said.

It’s also not clear what the price of launching Starship or New Glenn in the 2030s or 2040s will be, but it’s likely a small fraction of the total cost of a multibillion-dollar observatory.

In order to send any of these telescopes into deep space toward the L2 Lagrange point, where they can observe the universe away from interference from Earth, the spacecraft would need to refuel in orbit. NASA optics experts have questions about whether the refueling process could contaminate the telescope’s sensitive mirrors, Feinberg said. A telescope loitering in low Earth orbit waiting for its spacecraft to be refueled could also be exposed to extreme temperature fluctuations, which could put it at risk of damage.

“These are all considerations that we will have to understand over the next several years,” Feinberg said. “When we ask (SpaceX) for details, we feel like they’ll tell us when they figure these things out, but they can’t tell us these things right now. On the New Glenn side, it’s different, where what they’re planning to launch (on their first flight) will potentially get you to L2, So they are very close.”

Ultimately, if NASA wants to go bigger with the next generation of space telescopes, Starship could accommodate a folded mirror up to 10 to 12 meters wide, according to Feinberg. For New Glen, the upper limit is likely to be around 8 metres. Larger mirrors increase the collecting area of the telescope, giving it improved resolution for seeing smaller, fainter objects.

“I think we’re in a new situation,” Elvis said. “These launchers change what we can do in space, and at what cost. The way you design the mission has completely changed.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25550621/voultar_snes2.jpg)

More Stories

Watch a Massive X-Class Solar Explosion From a Sunspot Facing Earth (Video)

New Study Challenges Mantle Oxidation Theory

The theory says that complex life on Earth may be much older than previously thought.