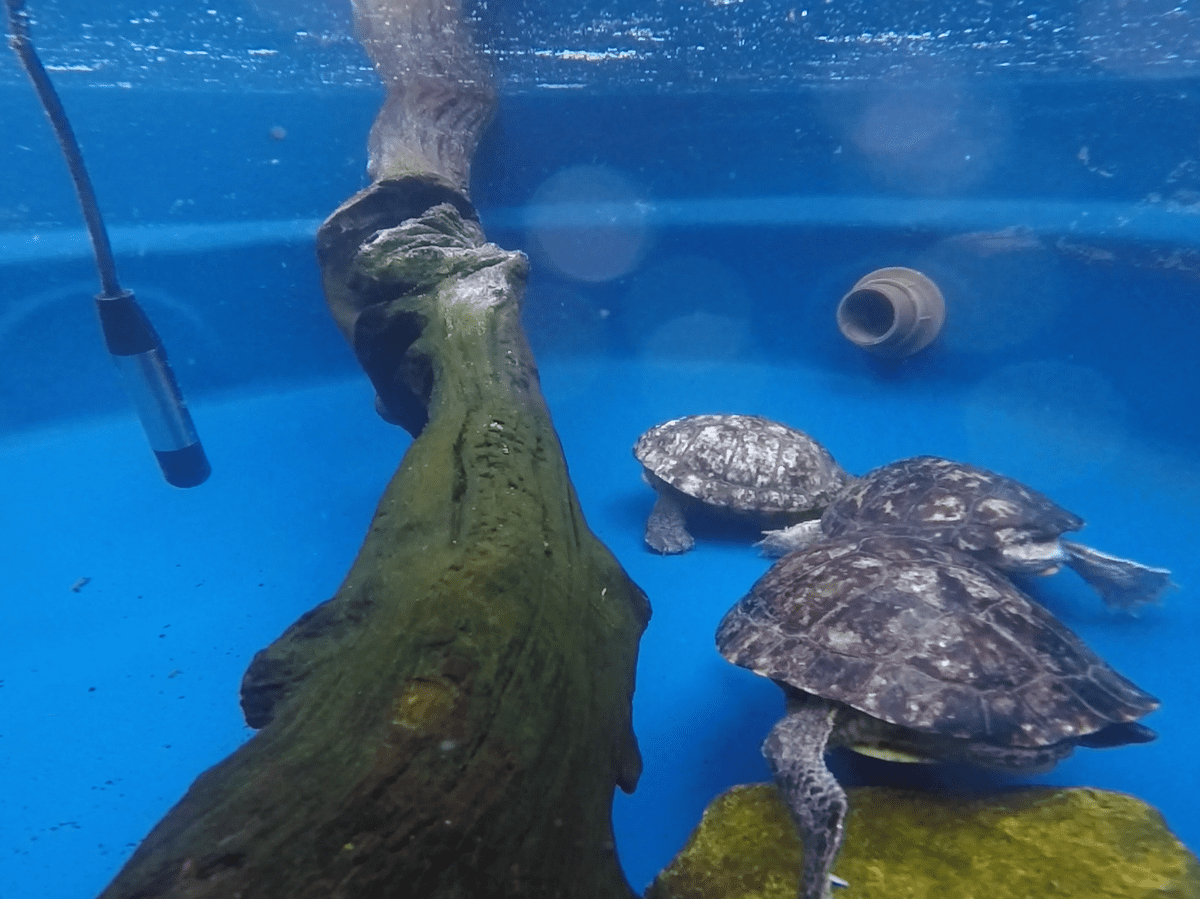

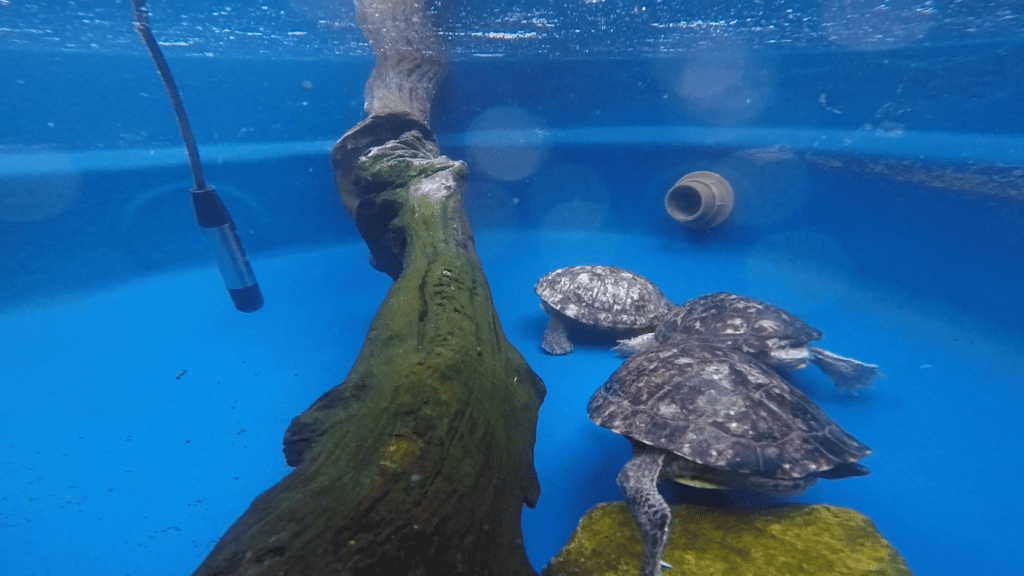

Gabriel Jorgewich Cohen set out to research whether turtle species — and other vertebrates thought to be silent — make sounds by recording their pet turtles. The microphone used for recording can be seen on the left.

Gabriel Georgić Cohen

Hide caption

Caption switch

Gabriel Georgić Cohen

Gabriel Jorgewich Cohen set out to research whether turtle species — and other vertebrates thought to be silent — make sounds by recording their pet turtles. The microphone used for recording can be seen on the left.

Gabriel Georgić Cohen

In the animal kingdom, some creatures are famous for the sounds they make – birds and their songs, cats and mios, frogs and their ribs.

But some animals are more mysterious. Do you talk to turtles? What about other lesser known vertebrates like tuatara, caecilians and lungfish?

The answer is yes, according to new paper in Nature Communications Providing evidence that many species thought to be silent do in fact speak – and researchers have recorded it on tape.

Want to hear the proof? this is the sound of Southern New Guinea Giant Softshell Turtle. And the This is a snakeA limbless amphibian that lives underground.

Gabriel Georgić Cohen, an evolutionary biologist working on a PhD at the University of Zurich, is the paper’s lead author.

He explains that this project started after he read about an Amazon turtle making noises, and began wondering about the tiny sounds his pet turtle makes. He reached out to a researcher at his former university in Brazil who devised a tool that would be crucial to the research.

“He’s developed a kind of water microphone, which is pretty much an underwater microphone,” Jorgewich Cohen explains. “I took her home and started recording my pets. I already heard she was making a lot of noise.”

The project was running. He traveled to eight or nine institutions in five countries, in his quest to record species of animals that were often thought of as silent. He recorded fifty species of turtle, as well as caecilians, tuatara (a reptile currently found only in New Zealand) and lungfish (fish that can breathe air).

And it turns out, no one Some of them were silent. “Actually, every animal I recorded was making sounds,” says Jorgewich Cohen.

He says the findings point to a common ancestor about 407 million years ago.

“Sometimes it’s surprising that we still don’t know much about things that are not necessarily uncommon but that live with us,” says Neil Kelly, a paleontologist at Vanderbilt University.

Kelly says the paper’s conclusion, mapping these sounds on the evolutionary tree, makes sense. He notes that there have been unique challenges in trying to study animal sounds over millions of years.

“It’s very difficult to trace that in the fossil record, because it is clear that sounds do not fossilize, and most acoustic equipment is based on soft tissue,” he notes.

The tuatara – a rare reptile found only in the wild in New Zealand – was registered at Chester Zoo in the UK last year.

Gabriel Georgić Cohen

Hide caption

Caption switch

Gabriel Georgić Cohen

The tuatara – a rare reptile found only in the wild in New Zealand – was registered at Chester Zoo in the UK last year.

Gabriel Georgić Cohen

It is important to note that sound production and hearing are two different things. Snakes, for example, are famous for their hissing sounds. But they are not thought to be able to hear themselves – or each other – hissing.

John Wiens, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Arizona, says that a tortoise’s making of sounds doesn’t necessarily mean that it communicates in this way.

“I think there’s some confusion between making sounds and communicating with voice,” he says of the paper.

Jorgewich Cohen says that although the research team isn’t sure what all the sounds they collected mean, they used several strategies to identify the sounds used to communicate – including using cameras to associate sounds with behaviors that could show some kind of intent, and only include the sounds that are It is frequently produced and appears to be related to social behaviour.

Wiens says recording these sounds is an important step toward greater understanding.

“If you don’t record and report these sounds, there is no reason for anyone to study vocal communication in these things,” he says. “You don’t even know they’re making sounds.”

The next step, he says, is to find out what these animals might actually say.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25550621/voultar_snes2.jpg)

More Stories

Watch a Massive X-Class Solar Explosion From a Sunspot Facing Earth (Video)

New Study Challenges Mantle Oxidation Theory

The theory says that complex life on Earth may be much older than previously thought.