A new study says that if we want to create the conditions necessary for life on another planet, let alone life itself, we must stop hoping for carbon in its atmosphere. Instead, it is the absence of carbon in the atmosphere, or at least the lack of it, that could be a sign that we are getting closer.

All life on Earth depends on five elements: carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and phosphorus. Among these elements, carbon is particularly crucial.

Thus, it makes sense to be on the lookout for their presence in the atmospheres of planets that we believe may support extraterrestrial life. However, a multidisciplinary team believes we may be going too far back. Atmospheres with very little carbon might be the signals we're looking for that the planet has a good chance of life.

Water, which is made up of hydrogen and oxygen, is another crucial element to look for, but only if it is in liquid form. Professor Julian de Wit from MIT is part of a team that suspects that liquid water and atmospheric carbon don't go well together.

“[A]All the features talked about so far [as indicators of life] De Wit said in a statement. “Now we have a way to find out if there is liquid water on another planet. This is something we could get to in the next few years.”

Planets in a given star system would form with similar amounts of carbon, researchers say. “If we see a planet with less carbon now, it must have gone somewhere,” said co-author Professor Amory Triwood from the University of Birmingham. Heavier elements may be trapped in the planet's core, but carbon is too light for that. “The only process that can remove this much carbon from the atmosphere is a powerful water cycle involving oceans of liquid water,” Triaud continued.

The idea goes against our intuition: carbon in the atmosphere could indicate its abundance at the surface, which is what life needs. However, a quick look at the planets on either side of us shows that there may be something behind it. Venus has a thick atmosphere that is 96.5% carbon dioxide, but it is certainly not hospitable to life. Between the runaway global warming the gas creates, and the acidity it produces, carbon dioxide is the biggest problem.

On the other hand, the biggest obstacle to life on Mars may be how thin its atmosphere is, but what it contains is mostly carbon dioxide, so there doesn't seem to be a carbon signal there to be found.

Meanwhile, until humans entered the picture, carbon dioxide and methane concentrations in Earth's atmosphere were very low. Some of the lost carbon was lurking in the bodies of living organisms. “Biology, as we know it, not only produces chemicals but also consumes them,” the authors note. There is also a lot of it that dissolves in the oceans and settles on the seafloor, where it eventually turns into rock. The authors state that this roughly matches the amount found in the atmosphere of Venus.

“We believe that if we detect carbon depletion, it would likely be a strong sign of the presence of liquid water and/or life,” De Wit said. On the other hand, too much carbon dioxide would be what the team calls a biosignature.

Knowing this would be of no use if we couldn't detect carbon levels in a planet's atmosphere, but it's something the James Webb Space Telescope and upcoming telescopes can increasingly do, especially for planets that transit their star from our location. “CO2 is a very powerful observer in the infrared, and can be easily detected in exoplanetary atmospheres,” De Wit explained. The authors suggest that collecting data from ten transits should be sufficient for planets around the closest stars.

If an individual planet has little carbon in its atmosphere, this could be attributed to a quirk in the cloud from which the system formed. However, when the atmospheres of more than one planet can be compared, as scientists hope to do with TRAPPIST-1, the discrepancies can be very suggestive.

However, while this decrease in carbon dioxide2 It might indicate the possibility of life, but it would not be evidence that it evolved. To achieve this, other biosignatures are needed, and the team suggests that ozone should be a priority. Ozone refers to the constant replenishment of the atmosphere with molecular oxygen, which is difficult to explain without the presence of widespread photosynthetic life. On the other hand, O2 Although particles are more abundant in Earth's atmosphere, they emit radiation in a noisier part of the spectrum.

The study is published in Nature astronomy.

“Amateur organizer. Wannabe beer evangelist. General web fan. Certified internet ninja. Avid reader.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25550621/voultar_snes2.jpg)

More Stories

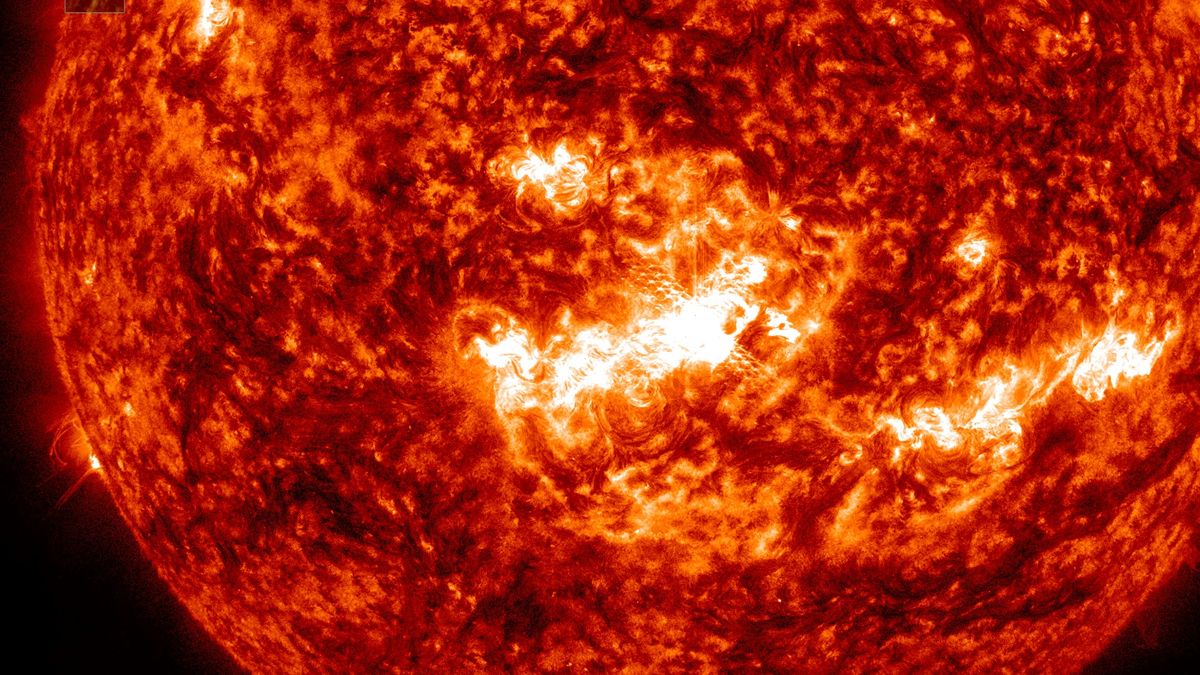

Watch a Massive X-Class Solar Explosion From a Sunspot Facing Earth (Video)

New Study Challenges Mantle Oxidation Theory

The theory says that complex life on Earth may be much older than previously thought.