Devins, Massachusetts. The machines are 20 feet high and weigh 60,000 pounds and represent the technological frontier of 3D printing.

Each machine deploys 150 laser beams, projected from a gantry and rapidly moving back and forth, making high-tech parts for corporate customers in areas including aerospace, semiconductors, defense and medical implants.

Parts of titanium and other materials are created layer by layer, each as thin as a human hair, up to 20,000 layers, depending on the part design. The machines are sealed. Inside, the atmosphere consists primarily of argon, which is the least reactive of the gases, reducing the chance of impurities causing defects in part.

The 3D-printing foundry in Devins, Massachusetts, about 40 miles northwest of Boston, is owned by Vulcan Forms, a startup that grew out of MIT. It has raised $355 million in project financing. Its workforce has jumped sixfold in the past year to 360, with recruits from major manufacturers such as General Electric, Pratt & Whitney and technology companies including Google and Autodesk.

“We’ve proven our success in technology. What we have to show now is that we have strong financials as a company and that we can manage growth,” said John Hart, co-founder of VulcanForms and professor of mechanical engineering at MIT.

For 3D printing, which has its origins in the 1980s, technological, economic, and investment trends may finally be in place for the industry’s commercial penetration, according to manufacturing experts, business executives, and investors.

They say 3D printing, also called additive manufacturing, is no longer a new technology for a few consumer and industrial products, or for making prototype design concepts.

“It is now a technology that is beginning to deliver industrial-grade product quality and volume printing,” said Jörg Bromberger, a manufacturing expert at McKinsey & Company. He is the lead author of a recent report by the consulting firm titled, “Massification of Additive Manufacturing.”

3D printing refers to doing something from the ground up, one layer at a time. Computer-guided lasers melt powders of metal, plastic, or composite materials to create the layers. In traditional “subtractive” manufacturing, a block of metal, for example, is cast, and then part of it is carved into a shape using machine tools.

In recent years, some companies have used additive technology to make specialized parts. General Electric relies on 3D printing to make fuel nozzles for its jet engines, Stryker makes spine implants and Adidas prints a mesh sole for its high-end running shoes. Dental implants and orthodontic appliances are 3D printed. During the Covid-19 pandemic, 3D printers have produced emergency supplies of face shields and ventilator parts.

Experts say the potential today is much broader than a relative range of niche products. The 3D printing market is expected to triple to nearly $45 billion worldwide by 2026, according to Report by HubsMarketplace for Manufacturing Services.

The Biden administration is looking to 3D printing to help re-emerge American manufacturing. Elizabeth Reynolds, special assistant to the president for industrialization and economic development, said additive technology will be one of “the foundations of modern manufacturing in the 21st century,” along with robotics and artificial intelligence.

In May, President Biden traveled to Cincinnati to announce manufacturing additives forward, An initiative coordinated by the White House in cooperation with major manufacturers. The company’s initial five members — GE Aviation, Honeywell, Siemens Energy, Raytheon and Lockheed Martin — are increasing their use of additive manufacturing and have pledged to help their small and medium American suppliers adopt the technology.

The voluntary commitments aim to accelerate investment and build a broader domestic base for additive manufacturing skills. Because 3D printing is a high-tech digital manufacturing process, administration officials say, it plays a role in America’s strength in software. They add that additional manufacturing will make American manufacturing less dependent on casting and metalworking done abroad, especially in China.

Additive manufacturing also promises an environmental bonus. It is much less wasteful than traditional casting, forging and cutting. For some metal parts, 3D printing can cut material costs by 90 percent and reduce energy use by 50 percent.

Experts say industrial 3D printing has the potential to drastically reduce the overall cost of making specialized parts, if the technology can be made fast and efficient enough to mass-produce.

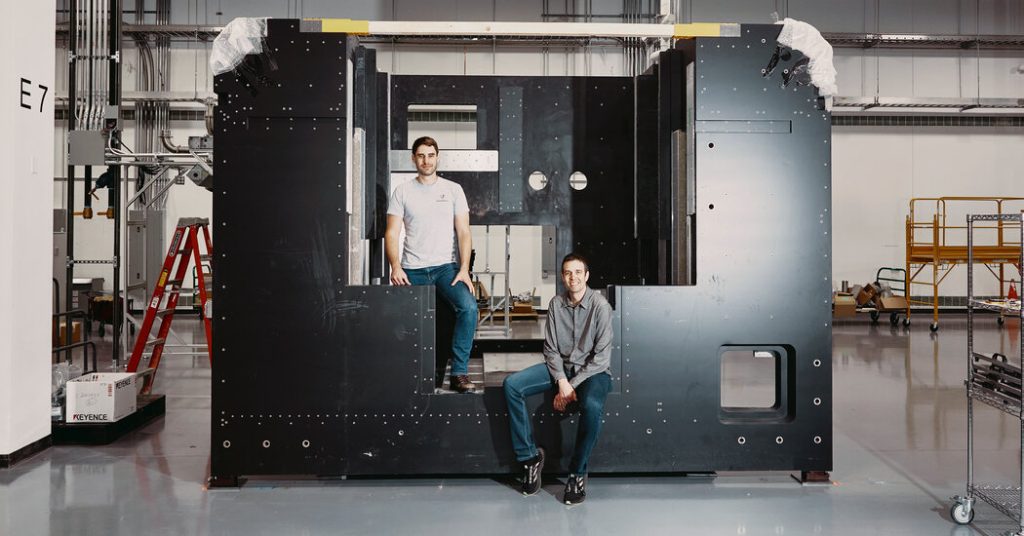

Vulcan Forms In 2015 by Dr. Hart and one of his graduate students, Martin Feldman. They’ve taken a new approach to 3D printing that uses more lasers than current systems. It will take innovations in laser optics, sensors, and software to design the complex choreography of lasers.

By 2017, they had made enough progress to believe they could build a machine, but they would need the money to do so. The pair are joined by Silicon Valley’s Anupam Gildial, a serial veteran who became part of the VulcanForms team. They got an initial round of $2 million from Eclipse Ventures.

The VulcanForms technology, mentioned Greg Reichow, partner at Eclipse, was trying to address the three drawbacks of 3D printing: too slow, too expensive, and too flawed.

The startup struggled to build the first machine that proved its concept was viable. But she succeeded in the end. Later versions grew larger, stronger, and more refined.

Vulcan Forms said its printers now generate 100 times the laser power of most 3D printers, and can produce parts many times faster. This printing technology is the company’s core intellectual assets, protected by dozens of patents.

But VulcanForms decided not to sell its devices. Its strategy is to be a supplier to customers who need custom parts.

This approach allows VulcanForms to control the entire manufacturing process. But it also compromises the fact that the additive manufacturing ecosystem does not exist. The company builds each stage of the manufacturing process itself, makes its own printers, designs parts, and does machining and final testing.

“We definitely have to do it ourselves – building a full range of digital manufacturing – if we are to succeed,” said Mr. Feldman, CEO. The factory is the product.

The Devens facility houses six of the giant printers. The company said that by next year, there should be 20. VulcanForms has explored four sites for a second plant. Within five years, the company hopes to establish and operate several 3D printing factories.

The ‘do-it-yourself’ strategy also magnifies the risk and cost of a startup. But the company convinced a list of high-profile recruits that the risk was worth it.

Brent Brunell joined VulcanForms last year from General Electric, where he was an expert in additive manufacturing. Mr. Brunel said the concept of using large arrays of lasers in 3D printing isn’t new, but no one has done it before. After joining VulcanForms and examining its technology, he said, “It was clear these guys were into the next architecture, and they had a successful operation.”

Next to each machine in the VulcanForms facility, an operator monitors its performance through a flow of sensor data and a camera image of the lasers in action, which are piped to a computer monitor. The factory sound is a low electronic buzzing sound, much like a data center.

The plant itself can be an effective recruitment tool. “I bring them here and show them the machines,” said Kip Wyman, a former senior manufacturing manager at Pratt & Whitney who is the chief operating officer of VulcanForms. The usual reaction is, “Heck, I want to be a part of that.”

For some industrial parts, 3D printing alone is not enough. It is needed for final heat treatment and metal fabrication. Realizing this, VulcanForms . acquired aroud machine this year.

Arwood is a modern machine shop that works mostly for the Pentagon, making parts for fighter planes, drones, and missiles. Under VulcanForms, the plan over the next few years is for Arwood to triple its investment and workforce, which currently includes 90 people.

VulcanForms, a private company, does not disclose its revenue. But she said sales were up quickly, while orders rose tenfold quarter by quarter.

VulcanForms’ sustainable growth will depend on increasing sales to clients such as Cerebraswhich manufactures specialized semiconductor systems for artificial intelligence applications. Cerebras sought out VulcanForms last year to help make a complex part for cooling powerful computer processors with water to cool them.

The semiconductor company sent VulcanForms a computer design drawing of the concept, an intricate network of tiny titanium tubes. Within 48 hours, VulcanForms was back with a portion, recalls Andrew Feldman, CEO of Cerebras. Engineers for both companies worked on further improvements, and the cooling system is now in use.

Accelerating the pace of experimentation and innovation is one of the promise of additive manufacturing. Mr. Feldman said that modern 3D printing also allows engineers to make new, complex designs that improve performance. “We couldn’t have made this water-cooling part any other way,” Mr. Feldman said.

“Additional manufacturing allows us to rethink how we build things,” he said. “That’s where we are now, and that’s a big change.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25550621/voultar_snes2.jpg)

More Stories

Bitcoin Fees Near Yearly Low as Bitcoin Price Hits $70K

Court ruling worries developers eyeing older Florida condos: NPR

Why Ethereum and BNB Are Ready to Recover as Bullish Rallies Surge