The moment a pumpkin toad leaps into the air, anything seems possible. A small frog, which is the size and color of a honeybee CloudberryHe has no problem launching himself off the ground. But when the pumpkin toad starts to rise, something goes awry.

The frog’s body begins to rotate, and its limbs are flattened like starfish. And then he falls, rolling mercilessly until he lands on his butt or head and inadvertently stops the wheels or rear.

“Some men just spin,” Andre Confetti, a graduate student at Brazil’s Federal University of Paraná, pretended by moving his finger in the air over a Zoom call. “Some men do this is Confetti added, waving his fingers in circles like a waterwheel.

“Frogs flutter in the air, in space,” said Amber Singh, who will soon become a master’s student at San Jose State University.

The pumpkin toad, which is a frog but not a frog, is so terrible at landing with its leaps that its utter incompetence has become the subject of scientific research. A team of researchers from the US and Brazil that includes Confetti and Singh say they have an answer: The little curls are so small that the fluid-filled chambers in their inner ears that control their balancing function somewhat ineffectively, eliminating the brave little hooppers. Over the lifetime of collision landings.

The paper Confirms that many species of pumpkin toad belonging to the genus of tadpoles are called humerusPresenting a “very unusual jump with uncontrolled landing behavior,” said Tess Kondis, a researcher at Carleton University in Canada who was not involved in the research.

Or, as Confetti said, “They’re not doing something right.”

It’s not easy being a vertebrate the size of a bee. Pumpkin braids made evolutionary trade-offs to be this small, like reducing the number of digits on their legs from five to three. Frogs, which are notorious for their moisture, dry out more quickly when they are young, said Rick Isner, a functional morphologist at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville and an author on the research paper. But sometimes it pays to be small: “For a can of pumpkin, an ant is a huge meal,” Eisner said.

frogs evolved The ability to jump before they develop the ability to land, which means that not all frogs have mastered the second part of the process. Eisner previously did research on a group of similar clumsy-tailed frogs, which jumped reasonably enough but landed in a full-face transplant.

When Marcio Bay, a researcher at the Federal University of Parana in Brazil, and author of the paper found Eisner’s research on the floundering frog, he emailed Eisner about pumpkin scales. Members of the Pie Lab have begun collecting tadpoles and other miniature frogs from the wild to watch them jump and (try to) land.

Pumpkin frogs live an elusive life. The frogs live and feed under fallen leaves in the Atlantic Forest of Brazil, which double in size, making them extremely difficult to study. “They are very small and secretive creatures,” Condez said. “Most of our knowledge about their behavior comes from rare observations in the field.”

Finding insect-sized frogs in Brazil is a daunting task. Although the pumpkin toad is as bright as the shito, the leaf litter is teeming with neon fungi and other orange-colored life. “It’s very difficult to catch under the leaf litter,” Confetti said. “Especially for me, because I’m color blind.”

Instead, the researchers had to listen to the frog’s call, which sounds a bit like a cricket. Back in Pie’s lab, the researchers placed each frog on a mirror surrounded by some barrier and filmed their jumping efforts. (Some had to be encouraged with a gentle flick of their little butt.)

When Eisner saw the footage, he burst out laughing. Then immediately consumed the problem at hand. The frogs were very far from the bouncing-tailed frogs on the frog family tree, which meant that the problem was not ancestral. So why couldn’t they land with one jump? “It wasn’t a ‘Eureka’ moment,” Eisner said. “It was a, ‘What the hell is going on here?’ moment.”

attributed to him: Rick Isner

attributed to him: Rick IsnerEisner proceeded to read a large number of scientific papers, including one Previous experience The researchers disturbed the vestibular systems of cane frogs, which are usually excellent hoppers. Hacked frogs displayed eerily similar landing problems as squash frogs.

Eisner wondered if the frog problem had reached a scale. Vertebrate organisms are able to balance and orient ourselves in the world because of our vestibular system: a complex system of fluid-filled chambers and channels in our inner ear. Moving our heads causes the fluid, called endolymph, to produce a force that deflects sensory hair cells and signals from our central nervous system to control our posture and movement. Despite the huge range of vertebrate body sizes, the size of these channels remains fairly constant. “Between a frog and a human or whale, they don’t change as much as you’d expect,” Eisner said.

The researchers suspected that the toad’s smaller body and smaller skull might restrict the size of the semicircular canals in their inner ear and prevent fluid from flowing freely. “When you take a tube and make it smaller and smaller and smaller, the resistance to fluid flow increases,” Eisner said.

David Blackburn, curator of herpetology at the Florida Museum of Natural History, and Edward Stanley, a museum associate scientist, conducted a cross-sectional survey of museum specimens of 147 species of frogs, including the largest (the Goliath frog), the smallest frogs (“there are two frog species in the run for the smallest frogs,” Stanley noted), and pumpkin frogs. The frogs were kept in a “standard frog position, somewhat rigid and not very flexible,” as Stanley described them. He packed preserved frogs in Ziploc bags packed with peanuts and wiped them with his million-dollar machine. Singh then provided 3D models of the semicircular canals of the frogs from the CT scan.

The resulting measurements revealed the semicircular canals of humerus The mini frogs in Bidofrine They were the smallest adult vertebrates, resulting in a loss of motor control and thus chaotic landings.

Researchers have considered other possible explanations. Perhaps the three-toed feet of the pumpkin braids slipped during the initial jump? Or perhaps its drooping leaves were meant to resemble fallen foliage, to deceive predators in search of a snack? The videos didn’t show as much slip on the frogs’ take-off, the researchers wrote, and the little braids didn’t stay still long enough to resemble a leaf.

CT scans also hinted that the plexuses may have developed some internal bony shields to make them safer when crashing. “They seem to be wearing a backpack that’s all bones,” said Stanley, referring to the pumpkin toad species. Brachycephalus ephippium. However, the pumpkin toad is likely to be more of a dribble than a jump. Eisner suggested that jumping is most likely an escape response, a way to hastily get one out of a dangerous situation. The saying goes that being bruised is better than being eaten. Plus, “You don’t have to worry about breaking bones if you’re the size of a housefly,” Eisner added.

Live pumpkin braids in Brazil atlantic forest, It is one of the most biologically diverse places on the planet. “Every mountain in southern Brazil has the potential to have a new kind of humerusSweets said. “We don’t know how much humerus We have it in our backyard.”

But 85 percent of the area has been deforested, and what remains is highly fragmented. “It makes me wonder how many of these species we’ll ever know about, because they’ve already disappeared,” Eisner said.

Perhaps the takeaway from Toad Pumpkin is that not everything has to be improved. Just because you’re bad at something doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do it, especially if you have a secret skeleton backpack and venomous glands. Even if the small jump of a pumpkin toad is the equivalent of a locomotive horse drawingThis does not mean that he should not walk or jump or stumble as he pleases in the damp litter of leaves in a disappearing forest. Each species should have the right to fail spectacularly, but on its own terms.

attributed to him: Rick Isner

attributed to him: Rick Isner

“Amateur organizer. Wannabe beer evangelist. General web fan. Certified internet ninja. Avid reader.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25550621/voultar_snes2.jpg)

More Stories

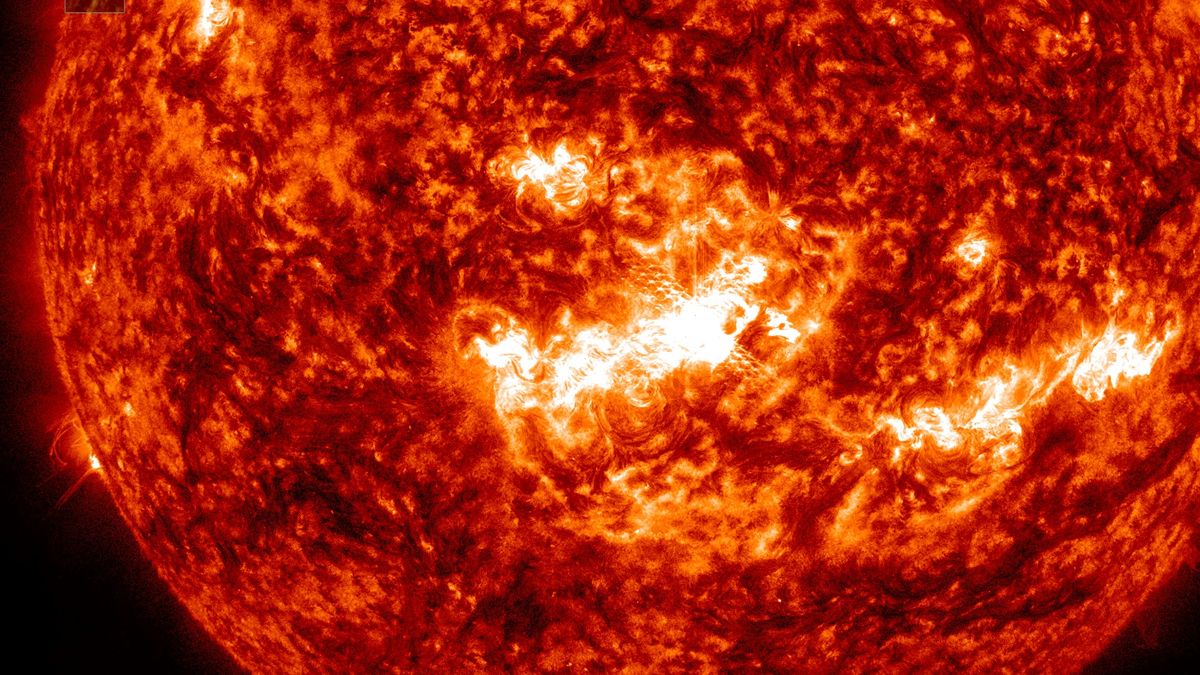

Watch a Massive X-Class Solar Explosion From a Sunspot Facing Earth (Video)

New Study Challenges Mantle Oxidation Theory

The theory says that complex life on Earth may be much older than previously thought.