Artist’s illustration of what a star “spaghetite” supermassive black hole looks like.

DESY, Scientific Communication Laboratory

Hide caption

Caption switch

DESY, Scientific Communication Laboratory

Artist’s illustration of what a star “spaghetite” supermassive black hole looks like.

DESY, Scientific Communication Laboratory

Astronomers have published an important discovery: it was a black hole “burping” from a young star that was observed to have ruptured in 2018, two years after which it had not ejected any such material.

How unusual is this?

“Very unusual,” Yvette Sendez, an astronomer at the Harvard and Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and lead author of paper, says NPR. “We’ve never really experienced this to this degree before.”

Researchers made the discovery when they did He used a powerful radio telescope facility – the New Mexico Very Large Array – to check about two dozen black holes where stars were scattered too close. This means that the material in the star has been broken up, or ‘muddy’. Such events are called tidal disturbance events, or TDEs.

What they found was that one of the TDEs (named AT2018hyz, if you’re curious) was emitting energy at an unusual speed and at a very surprising time: more than two years after the event.

This behavior differs from what has been observed in black holes before in two ways. First, the timing: It’s common to see radio emissions from black holes during the first few months after a star has been swallowed. And secondly, the energy released in this case does not quite match what astronomers have seen before.

In most cases of black holes swallowing stars, perhaps 99%, the outflow is lower in energy. And in 1% of cases, that flux is much more — a “very flushing event,” says Cendez, and it’s a very rare event.

But in this case? Between – about half the speed of light.

This represents “the first case where we’ve seen that kind of velocity associated with this event or that kind of flow,” Cendez explains. “But that also happened – our best estimate is about two years after this black hole ate the star is when this outpouring started – and that’s really exciting. It’s never been seen before.”

And scientists aren’t sure why this happens.

Sindez says that while the research team has been good at ruling out what’s going on no Causing this, they have no answer to what is there.

You’re probably wondering: Hey, I thought nothing could escape a black hole?

“There comes a point when you get so close to a black hole that you can’t escape the black hole – this is called the event horizon. But this material never crossed that boundary, according to our best estimates,” Seendez explains.

In other words, the star got close enough to the black hole to be torn apart – but not fall into that point of no return.

Team discovery means great new avenues of research.

“For theorists, that’s really exciting because suddenly it really opens up a new dimension in our understanding of physics and what’s possible. … They definitely need to act and tell me what’s going on because I’m also very curious,” Cendes laughs.

She says there are other black holes swallowing stars that need to be studied in greater depth. Such events can be More common than astronomers previously thought.

For Cendes, the discovery is what she and her fellow astronomers hope to find—a big thing.

“I’ve wanted to be an astronomer since I was 13,” she says. “Making this discovery has been a very exciting thing for me all my life. … It was definitely a lot of work and I certainly had a lot of good collaborators helping me get this out, but it was very, very rewarding which I wanted. It was so amazing “.

“Amateur organizer. Wannabe beer evangelist. General web fan. Certified internet ninja. Avid reader.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25550621/voultar_snes2.jpg)

More Stories

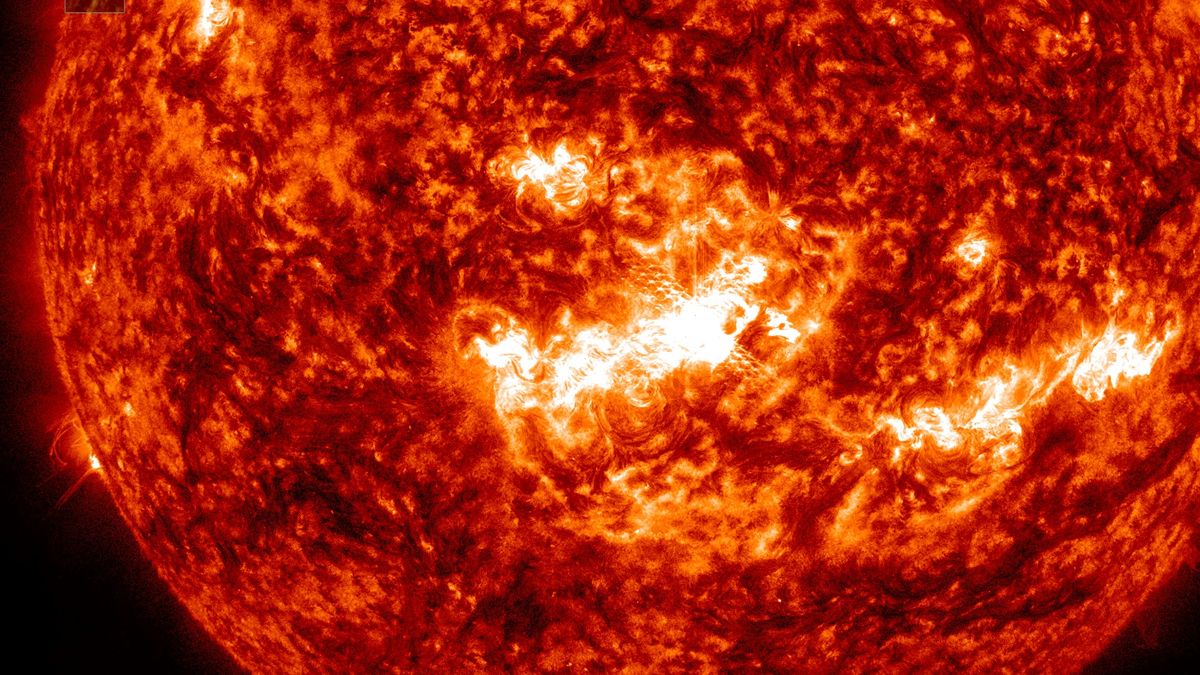

Watch a Massive X-Class Solar Explosion From a Sunspot Facing Earth (Video)

New Study Challenges Mantle Oxidation Theory

The theory says that complex life on Earth may be much older than previously thought.