In permafrost on the northern edge of Greenland, scientists have discovered the oldest known fragments of DNA, providing an unusual insight into an unusual ancient ecosystem.

The The genetic material dates back at least 2 million years – nearly twice the age of the massive Siberian DNA that carried previous record. and samples, described reported Wednesday in Nature, it came from more than 135 different species.

Together, they showed that an area just 600 miles from the North Pole was once covered in a forest of poplar and birch trees and inhabited by mastodons. The forests were also home to caribou and arctic hares. And the warm coastal waters teemed with horseshoe crabs, a species today that cannot be found farther north in Maine.

Independent experts hailed the study as a major advance.

“It’s almost magical to be able to deduce such a complete picture of an ancient ecosystem from small fragments of preserved DNA,” said Beth Shapiro, a paleoanthropologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

“I think it will blow people’s minds,” said Andrew Christ, a University of Vermont geologist who studies the ancient Arctic. “It definitely did for me.”

The discovery came after two decades of scientific gamble and frustrating setbacks.

One of the project leaders, Eske Willerslev, devised ways to pull DNA from sediments when he was a graduate student at the University of Copenhagen. In 2003, he and his colleagues studied a section of permafrost in Siberia, and found DNA from the plants Like willows and daisies dating back 400,000 years.

This discovery set a record for the oldest DNA, and many scientists doubted that anything much older could be found. But in 2006, Dr. Willerslev and Kurt Kjaer, a geologist at the University of Copenhagen, tried to defy the odds in northern Greenland. They made their way to a geological formation called Kappenhaven, a bare ridge as desolate as the surface of the moon. Previously, scientists found plant fossils estimated to be 2.4 million years old. Finding DNA in the sediment was amazing.

“If you want to move things forward, you need to take a few leaps,” said Dr. Kjaer.

The researchers dug up the permafrost and brought it back to Copenhagen to search for DNA. They fail to find any.

In later years, Dr. Willerslev and his colleagues had more success when they examined sediments and smaller bones from other parts of the world. Find out A wealth of ancient human DNA Help us reshape our understanding of the history of our species.

Along the way, the researchers have modified their methods for extracting DNA from ancient samples and updated the machines they used to sequence it. As they got better at hunting genes, they would take more Cape Copenhaven specimens for another shot.

But for years they failed again and again. From time to time they were disturbed by what looked like short fragments of DNA, which are called reads. The researchers couldn’t rule out the possibility that small fragments of DNA in Greenland, or even in their lab, had contaminated the reads.

Finally, after a major update in their technology, they found DNA in the samples in 2017. The permafrost turned out to be loaded with genetic material. Before long they had collected millions of DNA fragments.

“It was a breakthrough,” said Dr. Willerslev. “It was going from nothing or very little that you don’t know is real, to all of a sudden: it’s there.”

The researchers labeled the fragments with the DNA sequences of living species to see where they belong in the evolutionary tree. They found 102 different types of plants – including 78 previously recognized from fossils and 24 new species. Plant DNA painted a picture of forests dominated by poplars and birches.

Other sequences come from wild animals, including caribou, hares, industrial, geese, lemmings, and ants. The researchers also found marine species, such as horseshoe crabs, corals, and algae.

“It has replaced everything we imagined,” said Dr. Kjaer.

The researchers also searched the permafrost for new clues to the age of the fossils. They found layers in the sediments in which the minerals revealed that the Earth’s magnetic field had flipped. The age of those reflections helped the researchers determine that Cap Copenhaven is at least 2 million years old, but they were unable to establish a clear upper limit. “My gut feeling as a geologist is that he’s older,” said Dr. Kjaer.

The researchers ruled out the possibility that the DNA came from younger species contaminating the older permafrost. The DNA of the Cap Copenhaven birch trees lacked many of the mutations that living species have, indicating that they were ancient. The DNA from Kap Kobenhavn also had a distinct pattern of damage that only occurs when particles have been present in sediments for geological periods of time.

“It really helps show that this is indeed ancient DNA,” said Tyler Murchie, a postdoctoral researcher at McMaster University who was not involved in the new study.

The researchers were surprised by some of the species they found. Today, the caribou live in Greenland, as they do in most of the Arctic. But so far, their fossil record indicates that they evolved a million years ago. Their DNA now doubles their evolutionary history.

Love Dalen, a paleontologist from Stockholm University who last year unearthed the 1.2-million-year-old megalithic DNA in Siberia, is amazed that mastodons have appeared in Greenland. “What the hell are they doing there?” Asked.

Dalen noted that the earliest known 75,000-year-old mastodon fossils are in Nova Scotia — much younger than the Greenland DNA, and much further south than Cape Copenhaven. He said, “You can’t go north on land.”

Danish researchers determined that the mastodons of Greenland two million years ago belonged to a deep, previously unknown branch of the mastodon family tree. “It could mean that they are the ancestors of the late Pleistocene mastodons that we know of, or they could represent a new species,” Dalen said.

Ecologically, mastodons fit in well with the poplar and birch forests of Greenland, as they did in the forests of North America. While caribou are more common in the northern tundra, a subspecies lives in Canadian forests, providing clues to how ancient caribou thrived. But the presence of horseshoe crabs in shallow coastal waters indicates that the oceans and land were once remarkably warm.

Dr. Willerslev and his colleagues continue to study DNA in search of clues to how all these species were able to thrive a thousand miles north of the Arctic Circle. For example, trees had to live half a year in the dark. DNA preserved for two million years may hold the secrets of adaptation.

Scientists are also interested in how fragments of DNA manage to survive so long and defy expectations. Their research indicates that DNA molecules can cling to feldspar and clay minerals, protecting them from further damage.

Based on this discovery, the researchers are developing new methods that they hope will allow them to pull more DNA from the ancient sediments. Dr. Kjaer and his colleagues are excavating four-million-year-old sites in Canada in hopes of breaking their own record.

d said. Dallin, they may succeed. But the damage he and the Danish researchers found in the oldest DNA suggests to him that it would be impossible to find ancient genetic material older than about five million years. “This in no way indicates that there will be any DNA from fossils of the age of dinosaurs,” he said.

Dr. Crist said finding more DNA from places like Copenhagen Cape could help them better understand how human-caused climate change is in the Arctic. He said we should not assume that the region will resemble ecosystems further south. After all, the ecosystem of Cape Copenhaven two million years ago has no equal today.

“Life will adapt, but in ways we don’t expect,” said Dr. Christ.

“Amateur organizer. Wannabe beer evangelist. General web fan. Certified internet ninja. Avid reader.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25550621/voultar_snes2.jpg)

More Stories

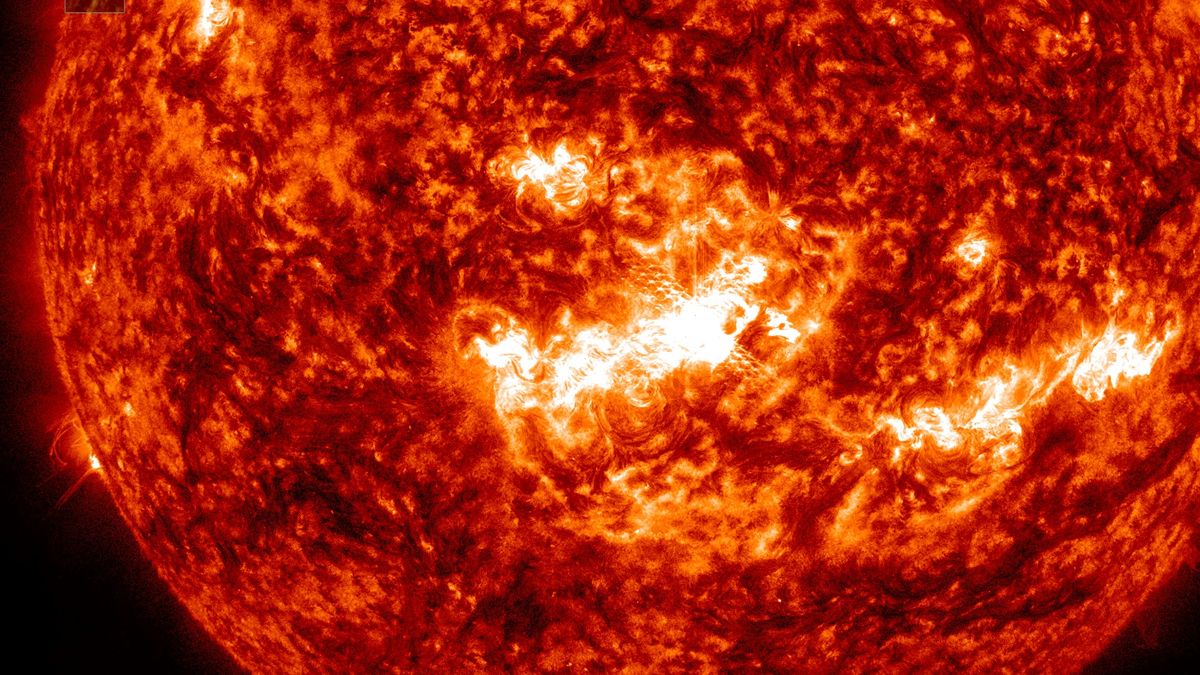

Watch a Massive X-Class Solar Explosion From a Sunspot Facing Earth (Video)

New Study Challenges Mantle Oxidation Theory

The theory says that complex life on Earth may be much older than previously thought.