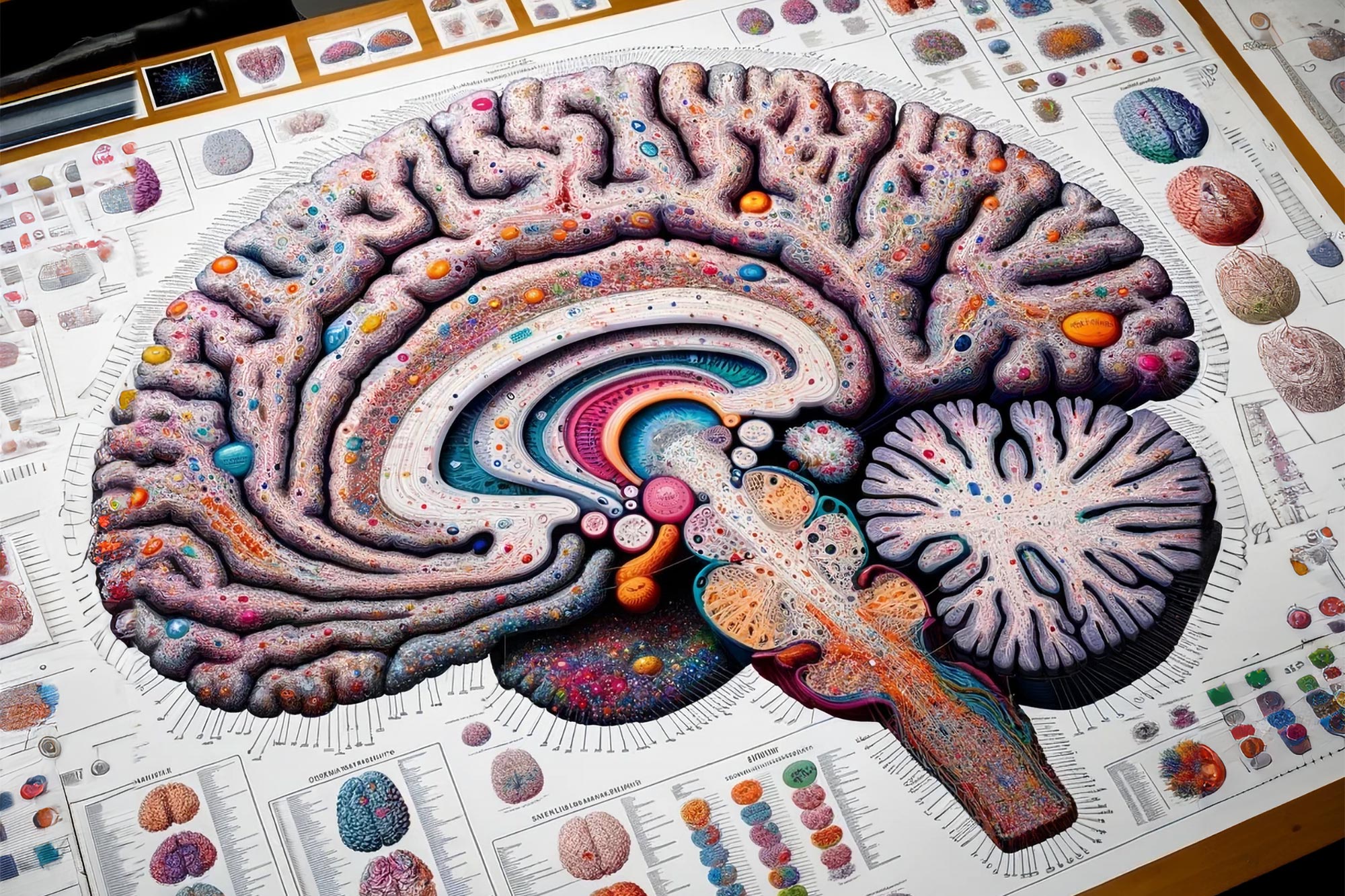

In a major collaborative effort, researchers from the University of California San Diego have mapped gene switches in different types of brain cells by analyzing more than a million human brain cells. This study, part of the BRAIN Initiative, sheds light on the relationship between certain cell types and neuropsychiatric disorders. They also used artificial intelligence to predict the effects of specific high-risk genetic variants.

Researchers map key genes and brain cell types linked to schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, Alzheimer’s disease Illness and severe depression.

In a large, multi-institutional effort led by the University of California San Diego (UCSD), researchers analyzed more than a million human brain cells to produce detailed maps of gene switching in brain cell types, revealing the connections between specific cell types. And various common neuropsychiatric disorders. The team also developed artificial intelligence tools to predict the impact of individual high-risk genetic variants among these cells and how they might contribute to disease.

“The human brain is not homogeneous. It is more like a mosaic of different cell types that look different and perform different functions. Identifying the different types of cells in the brain and understanding how they work will ultimately help us discover new treatments that can target individual cell types relevant to specific diseases. — Ping Ren, Ph.D

The BRAIN initiative and its goal

This pioneering research, which was presented in a special issue of the journal Sciences on October 13, 2023, is part of the National Institutes of Health’s brain research through the Advanced Innovative Neurotechnologies Initiative, or BRAIN Initiative, which was launched in 2014. The initiative aims to revolutionize understanding of the mammalian brain, in part, by developing new technologies . Neurotechniques for characterizing neuronal cell types.

Understanding cellular differences

Every cell in the human brain contains the same sequence DNABut different cell types use different genes in different amounts. This variation produces many different types of brain cells and contributes to the complexity of neural circuits. Learning how these cell types differ at the molecular level is crucial to understanding how the brain works and developing new ways to treat neurological and psychiatric diseases.

Complexity of the human brain

“The human brain is not homogeneous,” said lead researcher Ping Ren, Ph.D., a professor at the UC San Diego School of Medicine. “They are made up of a very complex network of neurons and non-neuronal cells, each of which performs different functions. Identifying the different types of cells in the brain and understanding how they work together will ultimately help us discover new treatments that can target individual cell types relevant to specific diseases.”

Main findings from the study

In the new study, the team of researchers analyzed more than 1.1 million brain cells across 42 different brain regions from three human brains. They identified 107 different subtypes of brain cells, and were able to link aspects of their molecular biology to a wide range of neuropsychiatric diseases, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, Alzheimer’s disease, and major depression. Researchers then use this data to create machine learning models to predict how specific sequence variations in DNA affect gene regulation and contribute to disease.

Continuing research and future endeavours

While these new findings provide important insights into the human brain and its diseases, scientists are still a long way from mapping the brain. In 2022, UC San Diego joined the Salk Institute and others in launching the Center for the Polygonal Human Brain Cell Atlas, which aims to study cells from more than a dozen human brains and ask questions about how the brain changes during development, over the course of people’s lives, and With illness.

“Expanding our work to a greater level of detail on a greater number of brains will bring us one step closer to understanding the biology of neuropsychiatric disorders and how they can be rehabilitated,” Ren said.

Reference: “A Comparative Atlas of Single-Cellular Chromatin Accessibility in the Human Brain” by Yang-Eric Li, Sebastian Pressel, Michael Miller, Nicholas D. Johnson, Zihan Wang, Henry Jiao, Chenxu Zhou, Zhauning Wang, Yang Xie, Olivier Poirion, Colin Kern, Antonio Pinto-Duarte, Wei Tian, Kimberly Seletti, Nora Emerson, Julia Austin, Jacinta Lucero, Lin Lin, Qian Yang, Quan Chu, Nathan Zemke, Sarah Espinoza, Anna Marie Yanni, Julie Niehus, Nick D., Tamara Kasper, Nadia Shapovalova, Danielle Hirschstein, Rebecca D. Hodge, Sten Lennarsson, Trygve Bakken, Boaz Levy, C. Dirk Keen, Jingbo Zhang, Ed Lin, Allen Wang, M. Margarita Behrens, Joseph R. Eker, Ping Ren, 13 years old October 2023, Sciences.

doi: 10.1126/science.adf7044

Co-authors of the study are: Yang Eric Li, Sebastian Pressel, Michael Miller, Zihan Wang, Henry Jiao, Chenxu Zhu, Zhaoning Wang, Yang Espinoza, Jingbo Zhang, and Allen Wang of the University of California, San Diego, and Nicholas D. Johnson Antonio Pinto Duarte, Wei Tian Nora Emerson, Julia Austin, Jacinta Lucero, M. Margareta Burns, and Joseph R. Ecker at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies. Kimberly Sillett and Steen Lennarsson at the Karolinxa Institute Annamarie Janni, Julie Nyhus, Nick Dee, Tamara Kasper, Nadja Shapovalova, Daniel Hirschstein, and Rebecca D. Hodge Trygve Bakken, Boaz Levy, and Ed Lin at the Allen Institute for Brain Science and C. Dirk Kane in University of Washington Seattle.

The study was previously supported National Institutes of Health (Grants UM1MH130994, U01MH114812, U54HG012510 and S10 OD026929), National Science Foundation (Grant OIA-2040727); and the Nancy and Buster Alford Endowment, the Life Sciences Research Foundation, as well as gifts from Google, Adobe, and Teradata.

“Amateur organizer. Wannabe beer evangelist. General web fan. Certified internet ninja. Avid reader.”

More Stories

Boeing’s long-awaited Starliner is ready for its first test flight to the International Space Station

Starlink – Starliner dual head? SpaceX and Boeing Starliner target on Monday

The Starliner test mission is well underway, and the rocket is on the launch pad