During the Ars Frontiers conference earlier this month, former NASA Deputy Administrator Lori Garver spoke about her efforts to transform the space agency when President Obama took office.

Large bureaucracies resist change, of course, and NASA has been around for five decades in 2009. In particular, Garver and other Obama administration appointees have sought to help NASA tap into the country’s nascent commercial space industry.

“The ongoing momentum of the status quo is there for most government contracting because the people who get paid to do something don’t care about cost-cutting,” Garver said. She explained that this is because changing the funding mechanism could mean that a certain part of NASA receives less funding.

The Commercial Space Initiative began under Mike Griffin in 2005, and by the end of that decade there was grudging acceptance within NASA and the broader space community that private companies should be tasked with moving cargo to the International Space Station. The Battle of Garver included extending this initiative to crew flights, and there was greater resistance to this idea. The Astronauts’ Office was largely opposed, and so was the majority of the traditional, well-established space industry.

“Dan Goldin, who was the head of NASA in the 1990s, called it a giant self-licking ice cream cone,” Garver said. “Why would someone want to get rid of this sugar if they could just keep eating it? So it wasn’t popular. I wasn’t popular. Members of Congress who had jobs in their districts from traditional contractors fought change and never funded it entirely and actually tried to eliminate it.”

That decision, of course, proved correct when SpaceX transported its first astronauts to the International Space Station in 2020. On Friday, the second commercial crew provider, Boeing, demonstrated its ability to dock with the space station. The company should begin flying crews in 2023.

Garver said the commercial crew’s primary goal is to lower the cost of getting people into orbit. Safety remained paramount, of course, but she and others felt private companies were ready to take over from the government, which had been sending humans into orbit since the Mercury Program in the early 1960s.

“Historically, if you look at the NASA budget and the number of astronauts we’ve flown with, we’ve spent about a billion dollars per astronaut,” she said. “We’ve moved about 350 people into space since Apollo, and spent about $350 billion. SpaceX now charges $55 million per seat. As a public policy initiative, it was all about lowering the cost of getting into orbit, getting the best value for taxpayers, and letting NASA spend Its billions on things unique to its mission.”

More than a decade after these cargo and crew programs began, NASA’s commercial space industry is helping the United States stay on the cutting edge of space flight. Investors spend billions of dollars annually to start new companies or support startups. In the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the capabilities of these new companies, such as providing synthetic aperture radar tracking of troop movements or Starlink’s online communications to war-torn communities, demonstrated the potential of this new sector.

But as Garver explained as she spoke, none of this was easy.

“It was absolutely amazing when we made our first budget request in the Obama administration and asked for this change — to have the private sector do it instead of the government,” she said. “Congress was angry. However when you went abroad, what was the response? I would say envy. And then I knew you were on the right track.”

List image by NASA

“Amateur organizer. Wannabe beer evangelist. General web fan. Certified internet ninja. Avid reader.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25550621/voultar_snes2.jpg)

More Stories

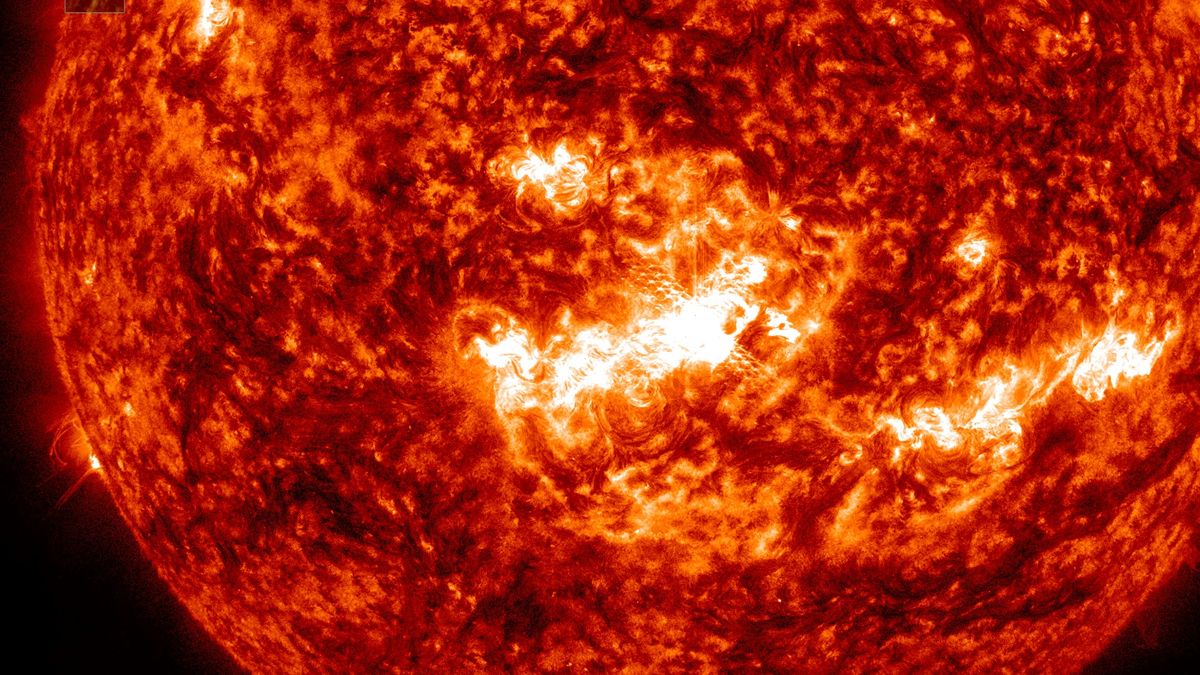

Watch a Massive X-Class Solar Explosion From a Sunspot Facing Earth (Video)

New Study Challenges Mantle Oxidation Theory

The theory says that complex life on Earth may be much older than previously thought.