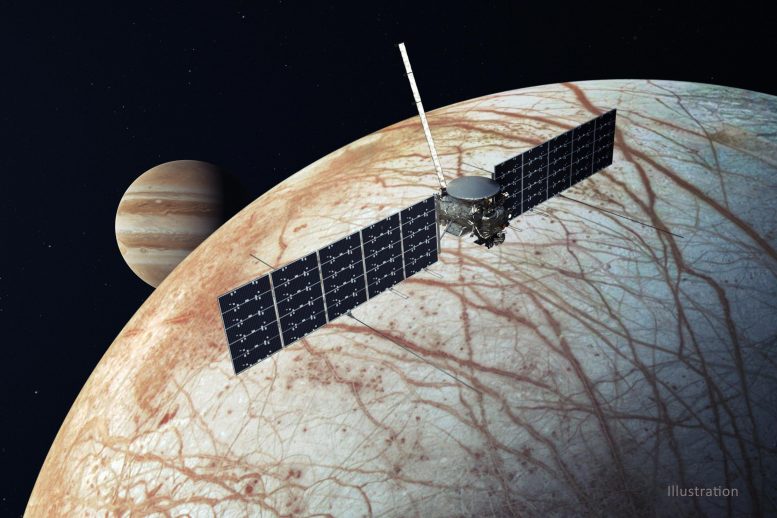

NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft, pictured in this illustration updated in December 2020, will orbit Jupiter on an elliptical path, approaching its moon Europa on each flyby to collect data. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

NASA‘s Europe Clipper’s mission focuses on solving transistor radiation problems as it prepares to launch on an expedition to Jupiter To explore the habitability of Europe.

The mission faces challenges related to radiation-resistant transistors, which have been shown to be less robust against Jupiter’s intense radiation. Tests at various NASA centers aim to address these issues.

Preparations are underway for the launch of NASA’s Europa Clipper mission. The spacecraft was delivered to the Kennedy Space Center in Florida in May, and the team has successfully installed the high-gain antenna.

Engineers working on NASA’s Europa Clipper mission continue to conduct extensive testing on the transistors that help control the flow of electricity on the spacecraft. The special versions used by Europa Clipper are radiation-resistant and designed to withstand between 100 and 300 kilorads (a rad is a unit of measurement for absorbed dose from ionizing radiation).

However, the mission team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (Jet Propulsion Laboratory) in Southern California, which runs the mission, is evaluating test data that suggests some transistors may be affected by much lower radiation levels in some conditions. They are concerned that some of these parts may not withstand the radiation of the Jupiter system, the most intense radiation environment in the solar system.

Radiation Challenges and Continuous Analysis

Testing is also being conducted at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. The Applied Physics Laboratory designed the spacecraft’s main body in collaboration with JPL and NASA Goddard.

The transistor problem came to light in May when the mission team was informed that similar parts could fail at lower-than-expected radiation doses. An industry alert was sent out in June 2024 notifying users of the issue. The manufacturer is working with the mission team to support ongoing radiation testing and analysis efforts to better understand the risks of using these parts on the Europa Clipper spacecraft.

Electronics Durability and Solutions

Data obtained so far suggests that some transistors are likely to fail in the high-radiation environment near Jupiter and its moon Europa because the parts are not as radiation-resistant as expected. The team is working to determine how many transistors might be vulnerable to failure and how they will perform during the flight. NASA is evaluating options to maximize the life of transistors in the Jupiter system. The initial analysis is expected to be completed in late July.

Radiation-hardened electronics are used across industries to protect spacecraft from radiation damage that can occur in space. The Jupiter system poses particular danger to spacecraft because of its massive magnetic field—about 20,000 times greater than Earth’s—which traps charged particles and accelerates them to very high energies, creating intense radiation that bombards Europa and other inner moons. The problem that could affect the transistors in the Europa Clipper appears to be a phenomenon that the industry was unaware of and represents a newly identified gap in the industry’s standard radiation qualification of transistor chips.

Mission objectives and future prospects

Europa Clipper’s launch period begins on October 10 and is scheduled to arrive at Jupiter in 2030, where it will conduct scientific investigations to understand the possibility of life on Europa while flying by the moon several times.

The total cost of the Europa Clipper mission is estimated at about $5 billion, making it one of the most expensive planetary science missions. This budget covers the development, launch, and operation of the spacecraft for the duration of its planned mission.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25550621/voultar_snes2.jpg)

More Stories

Watch a Massive X-Class Solar Explosion From a Sunspot Facing Earth (Video)

New Study Challenges Mantle Oxidation Theory

The theory says that complex life on Earth may be much older than previously thought.