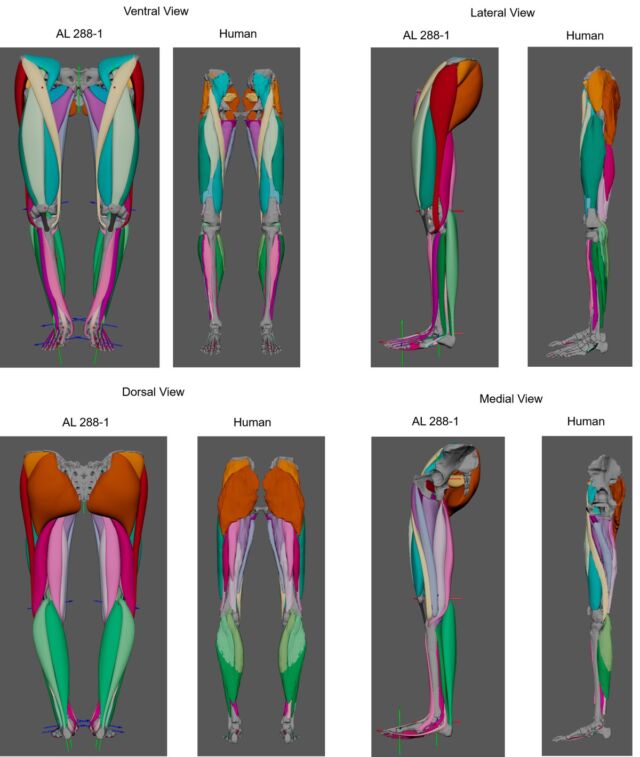

3D reconstruction of the muscles of the lower extremities Australopithecus afarensis Fossil AL 288-1, nicknamed “Lucy”. Credit: Ashley Weisman

One of the most famous fossils in the history of human evolution is known asLucy“which belongs to an extinct species called Australopithecus afarensis—a relative Homo sapiens who was one of the first hominins to walk upright. But scientists have long debated just how bipedal it could walk. Now, a 3D digital re-creation of Lucy’s muscular anatomy, combined with computer simulations, has reaffirmed that she was fully able to walk completely upright. The findings appear in a new research paper published in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

“Lucy’s ability to walk upright can only be known from a reconstruction of the trajectory and the space occupied by the muscles within the body,” said author Ashley Weisman, an archaeologist at the University of Cambridge. “We are now the only animal that can stand upright with straight knees. Lucy’s muscles indicate that she was as adept at walking on two legs as we are, while also likely being at home in the trees.”

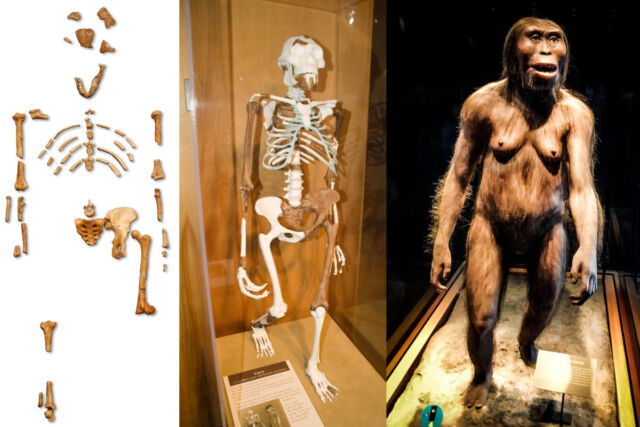

Lucy’s remains were found in 1974 in Ethiopia at a site called Hadar. Several paleoanthropologists—including Donald Johanson, Mary Leakey, and Eve Coppens—began scanning the site for signs of fossils related to the origin of humans. The first interesting discovery occurred in November 1971, when Johansson found a fossilized upper tibia bone, near the lower end of the femur. Now known as AL 129-1 and dating back more than 3 million years, the angle of the knee joint indicated that this was a Hominids (now known as Australopithecus afarinsis) able to walk upright.

But a truly significant discovery occurred on November 24, 1974, when Johansson and fellow expedition member Tom Gray decided to examine the bottom of a small gully. Johansson discovered a fragment of arm bone, then part of the skull, then part of the femur. Further explorations over the next few weeks yielded many bones, including vertebrae, part of the pelvis, ribs, and jaw fragments, all of which belonged to the same hominids. All told, there were several hundred pieces of fossilized bone that made up 40 percent of the complete female skeleton. This was “Lucy,” aka AL 288-1, named after the 1967 Beatles tune “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” which was played loudly and repeatedly on a camp tape recorder.

Once all the pieces were put together, scientists were able to reconstruct Lucy, revealing that she was 1.1 meters (3 feet, 7 inches) long and weighed about 29 kilograms (64 pounds). Its brain was small, like that of a chimpanzee, but its pelvis and leg bones (including the brain hallux valgus) looked nearly identical to modern humans, which suggests that Australopithecus afarensis He was completely bipedal, that is, he stood upright and walked upright.

How Lucy died is the subject of heated scholarly debate. Controversial 2016 paper It was suggested that careful analysis of her bones revealed how she died – by falling to her death from a very tall tree – although other scholars (including Johansson) thought the evidence was tenuous at best. As we reported at the time, University of Texas-Austin anthropologist John Kappelman and his team performed full X-ray scans of Lucy’s bones, allowing them to create high-resolution 3D renderings and 3D prints of her skeleton.

Comparing the way her bones fragmented to contemporary X-rays of the fallen people, they conclude that the fragmentation of her leg bones was “green,” meaning that it occurred just before her death. Specifically, the joint in Lucy’s leg experienced severe compression of the kind you’d expect in someone who fell to their feet from a great height, possibly from a local tree where the nests may be up to 23 meters off the ground. However, skeptics have pointed out that the fossilization process often breaks bones exactly the way Lucy’s bones are broken, and animals fossilized at the same time as Lucy have similar fractures.

Ashley Weisman

There has also been much debate about the frequency and competence of Lucy and her colleague Australopithecus afarensis He walked. Specifically, Lucy had a much wider pelvis and shorter legs than a human, which some scientists have said would have affected her gait. A consensus has begun to emerge in recent years in favor of a fully erect gait, rather than a crouching, chimpanzee-style gait. Weismann decided to use computer simulations and muscle modeling in hopes of shedding more light on the issue.

It was partly inspired by the job From paleobiologist Oliver Demuth, who pioneered biomechanics 3D musculoskeletal models to Extinct archosaurs. Extinct species often leave behind fossilized bones and skeletons, and while a lot can be learned from those remains, one needs to find a way to recreate the overlying muscles to understand the biomechanics of how a particular species moves. Demuth first used the limb anatomy of extant species to create 3D musculoskeletal models of known animals and then simulated movements such as walking, running, jumping, and standing. Then he expanded and adapted these models for extinct animals.

Wiseman followed a similar path for her work on Lucy’s muscle reconfiguration. First, she relied on MRI and CT scans of adult humans, female and male, to map muscle pathways and create a 3D digital model of skeletal muscle. Next, I used recently published open-source virtual models of Lucy’s fossil to put her skeleton back together, showing how each joint could move and rotate. Finally, she layers muscle on top, drawing on her map of human muscle pathways, backed by a few telltale traces of scars from where muscles were once attached to Lucy’s fossilized bones.

A 3D polygonal model, guided by imaging scan data and muscle scarring, lower limb muscle reconstruction in Australopithecus afarensis Fossil AL 288-1, nicknamed “Lucy”. Credit: Ashley Weisman

The resulting model included 36 muscles in each leg. According to Wiseman, Lucy had calves and thighs much larger than modern humans. The main muscle was more than twice the size. 74 percent of Lucy’s thigh is made up of muscle tissue compared to 50 percent in humans. Wiseman concluded that Lucy’s knee extensor muscles would allow enough pressure to straighten the knee joints like modern humans, thus enabling Lucy to walk upright, as well as perform a range of other movements similar to chimpanzees and bonobos.

These findings add further evidence to the emerging scientific consensus, but Wiseman cautioned that this is not definitive proof that Lucy can walk frequently and effectively. “Lucy probably walked and moved in a way we do not see in any living thing today,” She said. “Australopithecus afarensis It may have roamed the open wooded grassland areas as well as the denser forests of East Africa some 3 to 4 million years ago. Lucy’s muscle reconstructions indicate that she was able to exploit both habitats effectively.”

DOI: Royal Society for Open Science, 2023. 10.1098/RSOS.230356 (about DOIs).

“Amateur organizer. Wannabe beer evangelist. General web fan. Certified internet ninja. Avid reader.”

More Stories

SpaceX launches 23 Starlink satellites on Falcon 9 flight from Cape Canaveral – Spaceflight Now

Falcon 9 launches the Galileo navigation satellites

An unprecedented meteorite discovery challenges astrophysical models